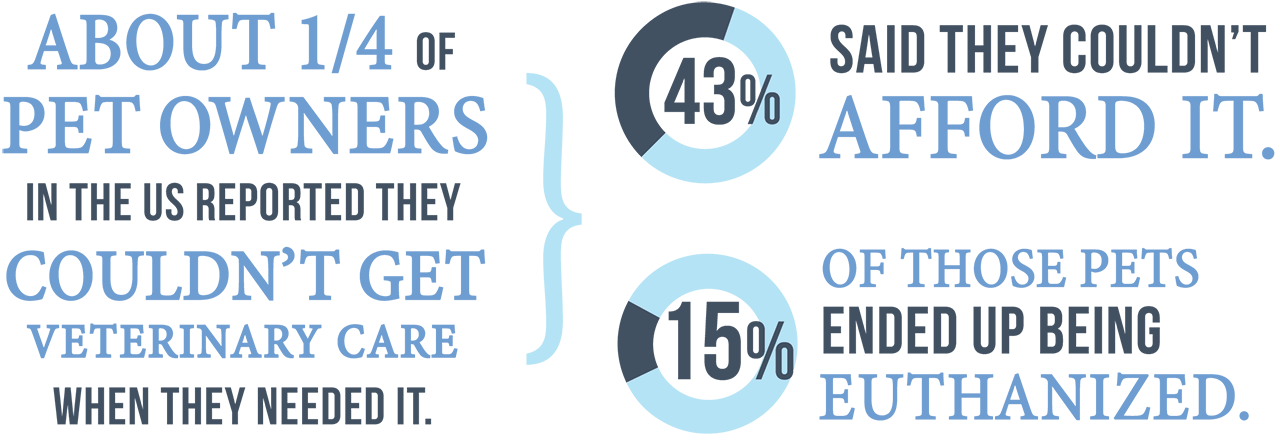

recent report by the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals1 revealed some mind-boggling statistics. About one-quarter of pet owners in the U.S. reported they couldn’t get veterinary care when they needed it and 43% said they couldn’t afford it. As a result, 15% percent of those pets ended up being euthanized. Every year, millions of pets, that otherwise are considered healthy, treatable and adoptable, are put down due to their owner’s inability to pay for treatment—a situation defined as “economic euthanasia.”

Limited access to veterinary care can have tragic consequences, and not only for pet owners who increasingly consider their companions as family members. Telling clients you can’t help them because they have no money is also emotionally taxing for the veterinary teams.

On average, survey participants reported euthanizing 17 pets per month. They were also asked to indicate the percentage of patients whose life was ended because their owners couldn’t afford treatment. The number was about 20%. Next, this data was compared with the burnout rate of the respondents.

While performing euthanasia, in general, was not related to burnout, a significant spike in the burnout rate was found of those staff members who encountered more cases of economic euthanasia. So it appears that euthanasia doesn’t have a negative impact on the well-being of veterinary professionals when it is perceived as a humane and peaceful way to discontinue a pet’s suffering in terminal cases. However, having to euthanize a pet while there is a viable medical alternative triggers burnout and compassion fatigue.

This evidence calls for immediate action to address the issue of economic euthanasia by overcoming barriers to veterinary care.

Alternative Funding and Flexible Payment Plans

Providing as many different payment options as possible and educating clients on these alternatives is key. Data shows that pet owners would be more likely to take their pet to the vet if they had the option to pay in installments. Consider having brochures for third-party lenders that offer this at the front desk so clients can take them home and learn more. Finances may be a sensitive subject, but multiple surveys revealed that clients expect and value conversations about the potential cost of care and their options.

Many practices are hesitant to offer their own payment plans to avoid bad debt. In this case, joining an online payment platform which manages payment plans for veterinary hospitals for a comparatively small fee is a great way to go. They have a system for collecting payments which increases the chances the debt will be paid. The process involves the veterinary hospital setting up an account online through which clients can apply for the payment plan. The hospital then makes approval decisions based on clients’ financial scores which are calculated by the platform.

Non-Profit and Angel Funds

Consider establishing a non-profit branch or a fund to provide financial assistance to under-served pet owners. There are many ways to support this fund, such as by collecting donations at checkout, offering staff to roll a certain percentage of their salary into the fund, hosting fundraising events, or by partnering with local businesses or brands. For example, non-profit organization Galaxy Vets Foundation5 collaborated with PetHub and partnered with veterinary hospitals across the U.S. that were selling pet ID tags to help animals in Ukraine.

To stretch your angel funds further, consider offering payment plans to clients with poor financial scores and use the funds to cover any defaults. Research shows that this can increase the impact of your funds tenfold.6

Pet Insurance

Pet insurance provides peace of mind and financial protection in case of unexpected veterinary expenses. Despite these benefits, pet insurance has not been widely adopted in the U.S. One reason for this is the perception that pet insurance is expensive, which can discourage some pet owners from signing up. Additionally, many pet owners may not be aware that pet insurance is an option, or they may not understand how it works. Various research suggests that pet owners would be more likely to purchase pet insurance if their veterinarian recommended it. And, data shows that pet insurance reduces the rate of economic euthanasia.7

Veterinary practices can play an important role in promoting pet insurance and increasing its adoption, thus lowering the chance that finances will get in the way of patient care. But first, start by educating yourself and your team on the available options. Order promotional materials from providers and offer them to clients. Incorporate discussions about pet insurance into routine care visits, especially with new pet owners.

Pet-Specific Care and Personalized Medicine

Although pets typically receive regular vaccinations and parasite control, genetic predispositions to certain illnesses are often overlooked. Consequently, ailments such as arthritis, dental disease, heart conditions, high blood pressure, kidney disease and diabetes are only diagnosed when they become clinically apparent. Many pet owners are unaware of the risks their pets face and do not seek personalized advice, so consider offering pet-specific screenings for the early detection of diseases. Client education on preventive and at-home care is especially important for new pet owners, and it’s a great way to better utilize your veterinary technicians.

Telehealth and Virtual Care

Having easy access to veterinary advice in a convenient form can encourage pet owners to seek care promptly, reducing the likelihood of an emergency situation arising or neglecting the symptoms altogether. Telehealth can also help improve compliance and ensure that pet owners follow post-treatment care instructions, reducing the risk of complications and the need for emergency care.

The lowest threshold to enter the telehealth arena is probably teletriage—a remote assessment of a patient’s condition by a veterinary professional to determine the care needed and provide assistance with immediate needs. This service doesn’t require a VCPR, so it can be performed by licensed technicians. And there are plenty of third-party providers to outsource from if you don’t have the internal capacity.

Encourage Open Communication

Staff members should feel comfortable speaking openly about their feelings and concerns related to economic euthanasia and ethical aspects of veterinary medicine. Encourage open communication by creating a safe and non-judgmental environment where staff can share their thoughts and feelings. Provide your team members with an option to opt out of certain cases if they are not comfortable with them.

Provide Training

Consider training staff on coping mechanisms for moral dilemmas and coaching with an emphasis on emotional and psychological wellness topics. Train leadership in emotional intelligence, how to empathize with the team members and how to support them in emotional situations.

Access to Counseling

If you offer an employee assistance program and it includes counseling services, make sure that employees are aware of this opportunity. Counseling can help staff members process difficult emotions and develop coping strategies.

By implementing these strategies, economic euthanasia in veterinary medicine can be reduced and more pets can receive the care they need without financial hardship for their owners.

- ASPCA. (2023, Mar 15). National Public Survey on Access to Veterinary Care & Telemedicine. ASPCA. https://aspca.app.box.com/s/prwqamoynk8a6anq5hy7j77d4ug21bjf

- Galaxy Vets. (2023, Mar 9). The Emotional Toll of Financial Stress, Work Environment, and Euthanasia. Galaxy Vets. https://links.galaxyvets.com/burnoutstudy

- Moses, L., Malowney, M., Boyd, J. (2018, Oct 15). Ethical conflict and moral distress in veterinary practice: A survey of North American veterinarians. J Vet Intern Med. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6271308/

- Kipperman B., Morris P., Rollin B. (2018, May 12). Ethical dilemmas encountered by small animal veterinarians: characterisation, responses, consequences and beliefs regarding euthanasia. British Veterinary Association. https://bvajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1136/vr.104619

- Galaxy Vets Foundation. https://galaxyvets.foundation/

- Cammisa, H., Hill, S. (2022, Aug 1). Payment options: An analysis of 6 years of payment plan data and potential implications for for-profit clinics, non-profit veterinary providers, and funders to access to care initiatives. Frontiers in Veterinary Science. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2022.895532/full

- Boller M., Nemanic T., Anthonisz J., et. al. (2020, Dec 8). The Effect of Pet Insurance on Presurgical Euthanasia of Dogs with Gastric Dilatation-Volvulus: A Novel Approach to Quantifying Economic Euthanasia in Veterinary Emergency Medicine. Frontiers in Veterinary Science. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2020.590615/full