Photos by Dr. Colleen Duncan

n July 2023, the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) endorsed the World Veterinary Association’s position statement on climate which declared climate change a global emergency. In doing so, the AVMA signaled its full support for the veterinary industry to use every skill they had, and to develop new ones, to help create a future of resilience and innovation.

The AVMA reaffirmed its commitment to the One Health planetary health framework, which emphasizes protecting animal and public health from increasing temperatures and heat stress, extreme weather events, the pollution of air quality, threats of vector-borne diseases, food safety and security, water-related health issues and safeguarding mental health.

As veterinarians worldwide are defining and establishing their roles in helping to combat the health impacts of climate change on animals, veterinary colleges like Colorado State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences in Fort Collins, Colorado are working to educate the veterinarians of the future to be stewards of planetary health.

“Climate change makes all animals sick. We are critically close to the point of no return,” says Dr. Colleen Duncan, veterinarian and professor of preventative medicine and pathology at Colorado State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

“As public health professionals,” she continues, “veterinarians are uniquely poised to be contributors to climate change solutions, and they should be actively engaged in policy decision-making and empowered to take active roles in interdisciplinary conversations surrounding this important issue.”

“We need to change our consumptive behaviors to slow it down,” states Dr. Danielle Scott, a veterinarian who also has a master’s degree in Environmental Science and Management, is working towards her PhD in veterinary epidemiology and is doing a residency in preventative medicine at CSU’s James L. Voss Veterinary Teaching Hospital.

“Environmental health in general is my motivation,” Scott adds. “You can’t address it without addressing climate change. Climate change is the number-one threat to human and animal health. It’s the big neon sign.”

Preventive measures, such as protecting natural ecosystems, recycling and practicing environmental sustainability can not only minimize the impact of climate change on animals and humans, but promote resiliency.

“Healthy animals are more resilient to everything,” says Duncan. “Veterinarians and veterinary teams can do easy things like reducing their own environmental footprint in the workplace, landscaping, protect pollinators, expanding animal health care to those in need, and talking about that.

“Research shows that veterinarians are trusted messengers,” she continues. “The public is interested in hearing from them, and they can be champions of important sustainability messages. Talk to 4H and little kids about the importance of getting exercise and eating nutritious foods. Don’t pour things down a drain. It affects fish. Let water run naturally through watersheds uninterrupted. Talk about how important clean air is for everybody.”

Air pollution is a growing threat for animals, especially those who live outdoors most or all of the time. Dr. Scott is currently engaged in a research project to measure the vulnerability of animals to air pollution. She is studying the impact of air pollution on racehorses, specifically PM2.5 (particulate matter measuring 2.5 microns), which is the primary pollutant found in wildfire smoke. The fact that there is a large amount of existing, high-quality data on racehorses in general was one reason she decided to do her study on them.

“Racehorses are phenomenal athletes that live and train outdoors,” Scott says. “With their huge lung capacity, they inhale large amounts of air, which is even greater when they workout, and therefore can be at risk of experiencing higher levels of air pollution exposure. This allows them to serve as a sentinel species, which will provide opportunity to assess risk that can then be translated to other vulnerable species, as well as provide an understanding of the health risks from air pollution exposure.”

PM2.5 levels spike during smoke events, and they can get all the way into lung alveoli and cross into the bloodstream.

“Not many studies show the associated health impacts in animals,” she adds.

Her research, still in its preliminary stages, can be translated to other species to protect animal welfare, such as whether or not to train racehorses or race them during air pollution events, or whether other highly vulnerable animals like the average dog should be kept inside during pollution events, for example. However, the veterinary industry itself also needs to be part of the solution.

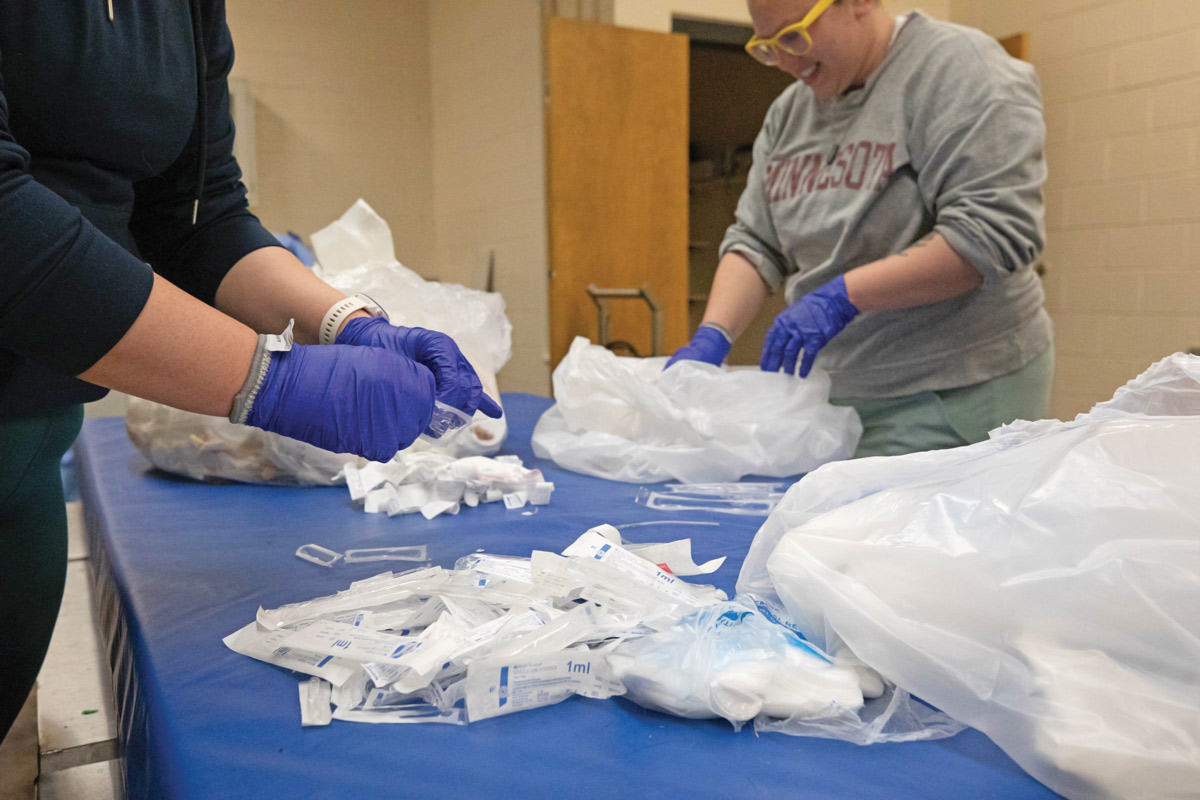

“We’re looking at how climate change affects health and how delivery of care contributes to climate change,” shares Scott. “It is a contradiction to protect animal health and use tools that are highly impactful in releasing greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change. For example, anesthesia is a greenhouse gas. There are alternatives to its use, such as the use of intravenous anesthesia and flow gas techniques.”

CSU’s veterinary college is even using its hospital as a case study in changing their environmental footprint.

“We’re getting a lot of support for it,” says Scott. “Everybody truly cares about it and wants to minimize the impact but need information on how to do it. We’re working to fill that gap. How can we deliver care without harm?”

They also work in collaboration with the Veterinary Sustainability Alliance, a non-profit organization that is working with the veterinary industry to reduce emissions that drive climate change, promote preventative medicine, protect the human-animal bond, protect natural habitat and more throughout North America.

“There are many little things, but collectively they can make a big difference,” says Duncan. “Reducing energy use by unplugging computers when they are not in use, recycling materials, not using plastic to package things, use renewables, re-evaluating how companies build and create things, and how supplies are transported can all make a difference. There’s an economic advantage for vets to be knowledgeable in environmental sustainability, too.”

In addition to the other changes and challenges they are working on to help prepare the veterinary industry for climate change, Colorado State University is building a new veterinary hospital. The building, which is scheduled for completion in 2026, will be a green-built LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design)-certified building, making it the first LEED-certified veterinary education facility in the United States. It will also be WELL certified. WELL-certified buildings meet high standards for construction that enhance the mental health of those who work in them.

The college is also implementing a new curriculum, which will focus more on preparing students to meet the needs of animals now and in the future, including an expansion of preventative care, environmental sustainability and more. But there is one thing will not change…

“It’s so important to keep people and their pets together,” emphasizes Scott. “Pets foster health.

“By the time the new hospital opens, the changes being made will have been embedded into our culture; our practices. It will be how things are done,” she concludes.