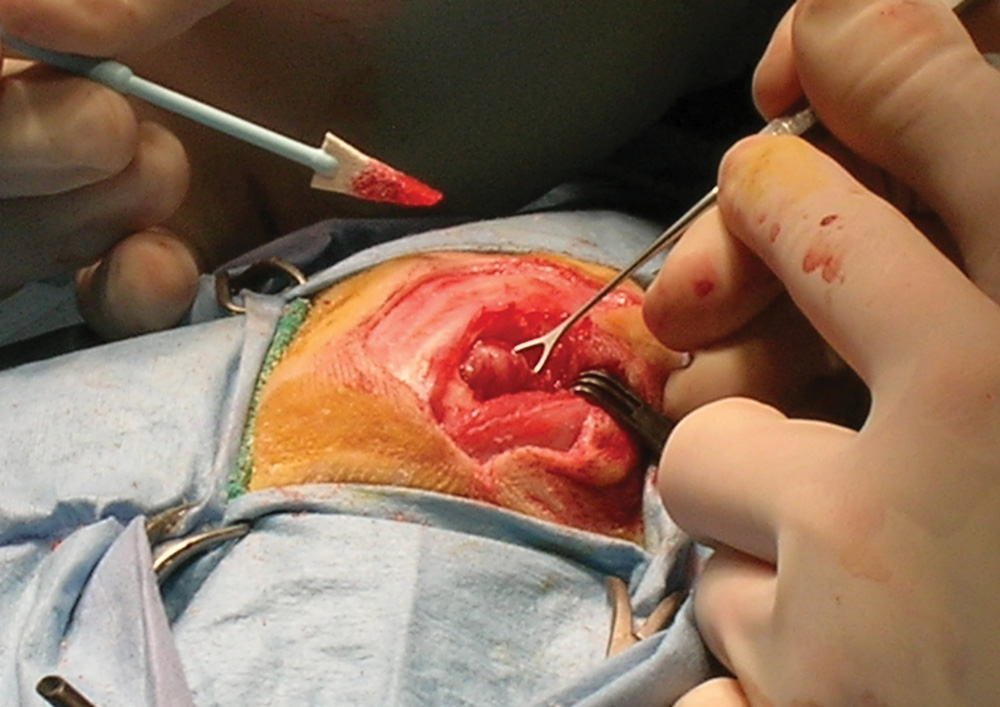

Photos provided by Dr. Karen Kline

o, long story short—a toad in the backyard and a Band-Aid, and the rest was history,” answers Karen Kline, DVM, MS, DACVIM (Neurology), when asked what early experiences pointed to a career as a veterinarian. “I was eight years old. The poor toad had been hit by a lawnmower and I attempted to help heal his/her wound by the application of the Band-Aid.

Fast forward, and I completed my undergraduate degree at Iowa State University and graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in Zoology,” she continues. “I then applied for veterinary school and did not get in, as I did not have enough large animal experience. So, I took the year off and worked as a veterinary technician at a small animal practice in Ohio. If I had not been accepted into veterinary school, my plan was to be a teacher either in middle school or high school and to teach the sciences. Thankfully I was accepted into The Ohio State University CVM after working as a technician for one year.”

Once in veterinary school, Dr. Kline had aspirations to own her own practice but experienced a change of tune when she completed a preceptorship at St. Marks Veterinary Hospital in New York City with Dr. Sally Haddock, who introduced Dr. Kline to the Animal Medical Center (AMC) in NYC.

As a specialty that most veterinarians are uncomfortable with, Dr. Kline says this is one of the reasons she chose to focus on neurology. In addition, she also wanted to learn more about how intricate the nervous system is and how her patients manage to survive such incredible injuries and illnesses, and it allows her to perform surgery.

A typical day for a veterinary neurologist is unpredictable, as neurologic animals can present as emergencies at any time of day or night. Dr. Kline’s main focus, along with teaching the veterinary students, is to present all available diagnostics and treatment options for her clients when their beloved pets are ill and need help.

“In both of my hospitals, I have in-depth conversations with my clients after a full neurologic and physical examination of their pet and then we discuss options for diagnostics and care,” she explains. “From there we will admit the pet and proceed on with necessary testing and interventions as needed.

In an ever-evolving world, the specialty of veterinary neurology is trying to keep pace with new innovations. Over the last 25 years, MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) has become the standard of care.

“I do think it is possible that other technologies that are used in human medicine, such as photon emitted tomography (PET scan) and CyberKnife radiation therapy, are in the forefront,” Dr. Kline notes. “With the emergence of AI, it is possible that this technology could augment teaching, patient care, data management and collection, and communication in the future.”

The core of neurology is the ability to localize the lesion in the patient so when the general practice veterinarian discusses the referral with a neurologist, they can describe the lesion and whether it is located in the brain, spinal cord or neuromuscular system. A plan of action can then be formulated and the veterinarian can discuss this with the owner.

“It is vital to know that many neurologic cases need immediate care and treatment (like seizures or paralysis) based upon clinical signs and the breed of the patient (for example, French Bulldogs),” Dr. Kline explains.

In addition, Dr. Kline has had the privilege of being a professor at two colleges of veterinary medicine. “My passion is teaching and I am hoping that I can help to develop a more refined hybrid model (faculty sharing) to benefit both academia and specialty veterinary practice,” she says.

Dr. Kline has been fortunate to travel both domestically and abroad as president of NAVC and as a member of their Board of Directors, but she also enjoys her home life on her five-acre property in Oregon with her husband, a retired large animal veterinarian, and their rescue Pit bull, Voodie.

To conclude, Dr. Kline leaves us with this advice: “The future of veterinary medicine depends on collaboration between colleges of veterinary medicine and specialty veterinary practices. Access to care has been difficult for our veterinary clients and it is our responsibility as clinicians and specialists to make sure that we follow our veterinary oath and provide quality care for all of our clients regardless of financial strata or demographic disparity.”