By Kathleen Cooney, DVM, CHPV, CPEV, DACAW

n order to perform euthanasia for pet patients in failing health, veterinarians first need to talk about the option. Diagnosing an animal with cancer and laying out medical options for clients is a transformative experience. It’s a delicate moment requiring strong communication skills and emotional intelligence. When delivering bad news like this, the mood is somber and respectful and naturally sets the tone for even deeper topics like euthanasia.

- “We’d like to talk with you about something that may be hard to hear.”

- “Based on everything you’ve shared with us, and knowing the seriousness of the condition, it’s important we understand that time is limited.”

- “Have you experienced cancer with other pets? What can you share with us about that experience?”

- “How do you envision the last days of their life? What does quality of life look like to you?”

- “If their comfort becomes hard to manage, how do you feel about releasing them from their body before things get too difficult, through euthanasia?”

- “They trust you to make whatever decision you feel is best, and this includes euthanasia.”

In fact, if you want people to hear your recommendations, you should let them share what’s on their minds first. What are their concerns? What are they hoping for now, knowing it’s cancer? People experiencing grief have a huge need to be understood but have little capacity to understand. The more they can get off their chest and diffuse tension, the better they will listen when you bring up the subject of euthanasia. When the space feels supportive and comfortable, veterinarians can gently lean into the euthanasia conversation.

This last one is my go-to statement when I want to bring up pet euthanasia. It’s not a question asking how they feel about it, but rather an honest sentiment that seems to reduce guilt over such a monumental decision. While some may consider it anthropomorphizing, I truly believe that when love is at the heart of a euthanasia decision, and significant suffering is expected, animals trust their owners to do what’s necessary.

Quantifying a pet’s day-to-day experiences can help clients see what the veterinarian sees or suspects. There are numerous quality-of-life scales for veterinarians to reach for,2 and while most are not validated, they can still effectively aid in opening up dialogue around a patient’s quality of life.3 If the situation is serious enough, the findings will help illustrate that euthanasia may be the best decision.

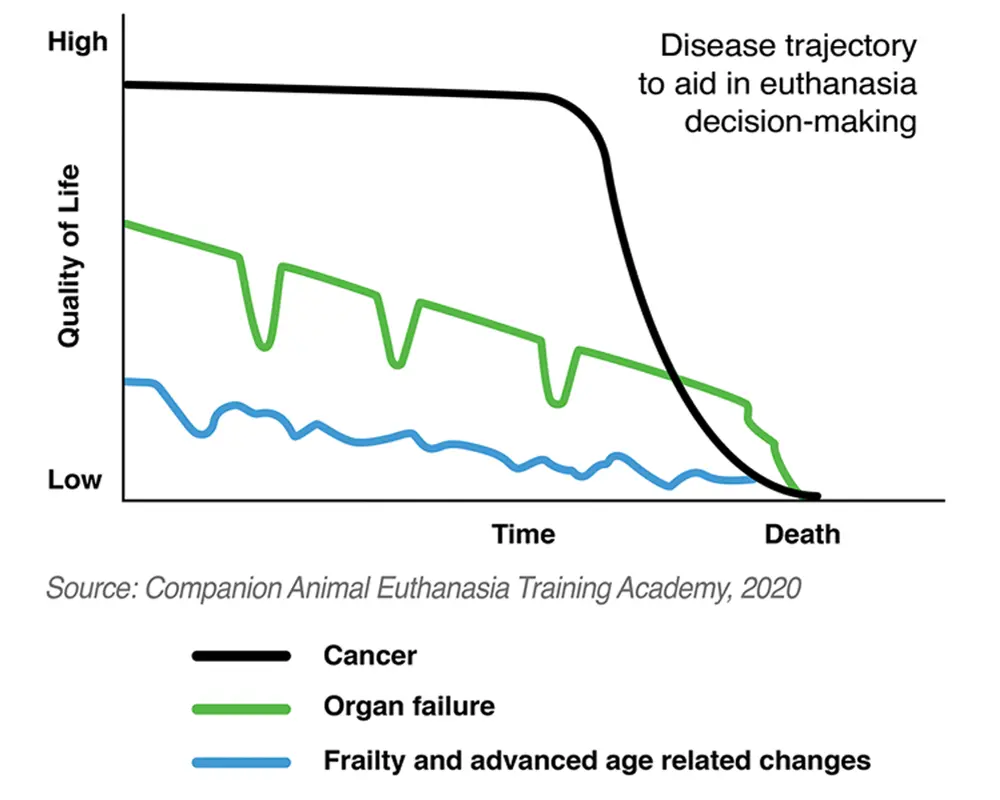

Disease trajectories can also help clients understand the normal course of conditions like cancer. They get a better feel of what’s ahead, and it makes bringing up the idea of euthanasia sooner rather than later more logical, especially when cancer cure or palliative care treatments aren’t possible. While the exact timing of a natural death from cancer is hard to predict, veterinarians follow patterns to guide clients on knowing when euthanasia is acceptable.

If they ask me what I would do if it were my pet, I answer honestly from their perspective, not mine: “Based on everything we know in this situation, I would feel OK with the decision. Very sad, but OK knowing it’s the best way to prevent further decline and struggle.”

The experience was so surprising to me. I was under the impression everyone knew what euthanasia meant, but here was a person who was unfamiliar with the word, and had he not asked for clarification, I may have proceeded.

In modern times with such ethnic and language diversity, gathering informed consent before carrying out euthanasia is vital. Beyond just conversation, my consent forms define euthanasia as “humanely terminating life.” I highly recommend this standard for all veterinary services performing euthanasia.

If they ask me what I would do if it were my pet, I answer honestly from their perspective, not mine: “Based on everything we know in this situation, I would feel OK with the decision. Very sad, but OK knowing it’s the best way to prevent further decline and struggle.”

Lastly, if you believe your patient has entered into the dying process, even if a few months away from a natural death, let the client know. Sometimes just stating the obvious has the greatest impact.5

No one likes to have this conversation—client or veterinarian. But if there is a sweet spot to euthanasia, it’s hearing about the beauty of the human-animal bond and knowing any physical and emotional struggle is coming to an end.

- Shaw, J. R., & Lagoni, L. (2007). End-of-Life Communication in Veterinary Medicine: Delivering Bad News and Euthanasia Decision Making. The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Small Animal Practice, 37(1), 95–108.

- Lap of Love Quality-of-Life Scale. https://www.lapoflove.com/how-will-i-know-it-is-time/lap-of-love-quality-of-life-scale.pdf

- Fulmer, A. E., Laven, L. J., & Hill, K. E. (2022). Quality of Life Measurement in Dogs and Cats: A Scoping Review of Generic Tools. Animals: an open access journal from MDPI, 12(3), 400.

- Matte, A. R., Khosa, D. K., Coe, J. B., Meehan, M., & Niel, L. (2020). Exploring pet owners’ experiences and self-reported satisfaction and grief following companion animal euthanasia. Veterinary Record, 187(12), e122–e122.

- Cooney, K. (2023, April). When Quality of Life Scales Aren’t Enough; Counseling clients who can’t let go. CAETA. https://caetainternational.com/when-quality-of-life-scales-arent-enough/