hose of us that care for unique species rely on every diagnostic tool in existence, and even then, we still have to get creative for our patients. For many of our species, we do not have a known normal for comparison or reported reference ranges to rely on. Even as a Board-Certified Specialist in Zoological MedicineTM, this can feel like a limitation to the care I can provide to my patients. The species we care for vary widely. In a single day, a veterinarian caring for non-domestic species might examine a rabbit, a bearded dragon, a blue and gold macaw, and an echidna. Each has vastly different physiology, anatomy and disease prediction.

Detailed Anatomy

Computed Tomography with contrast enhancement has opened a new chapter to understand the anatomy of these species antemortem.1 Searchable databases are currently under development. Once we know the normal anatomy, it helps us better recognize abnormal disease changes when they occur.2,3

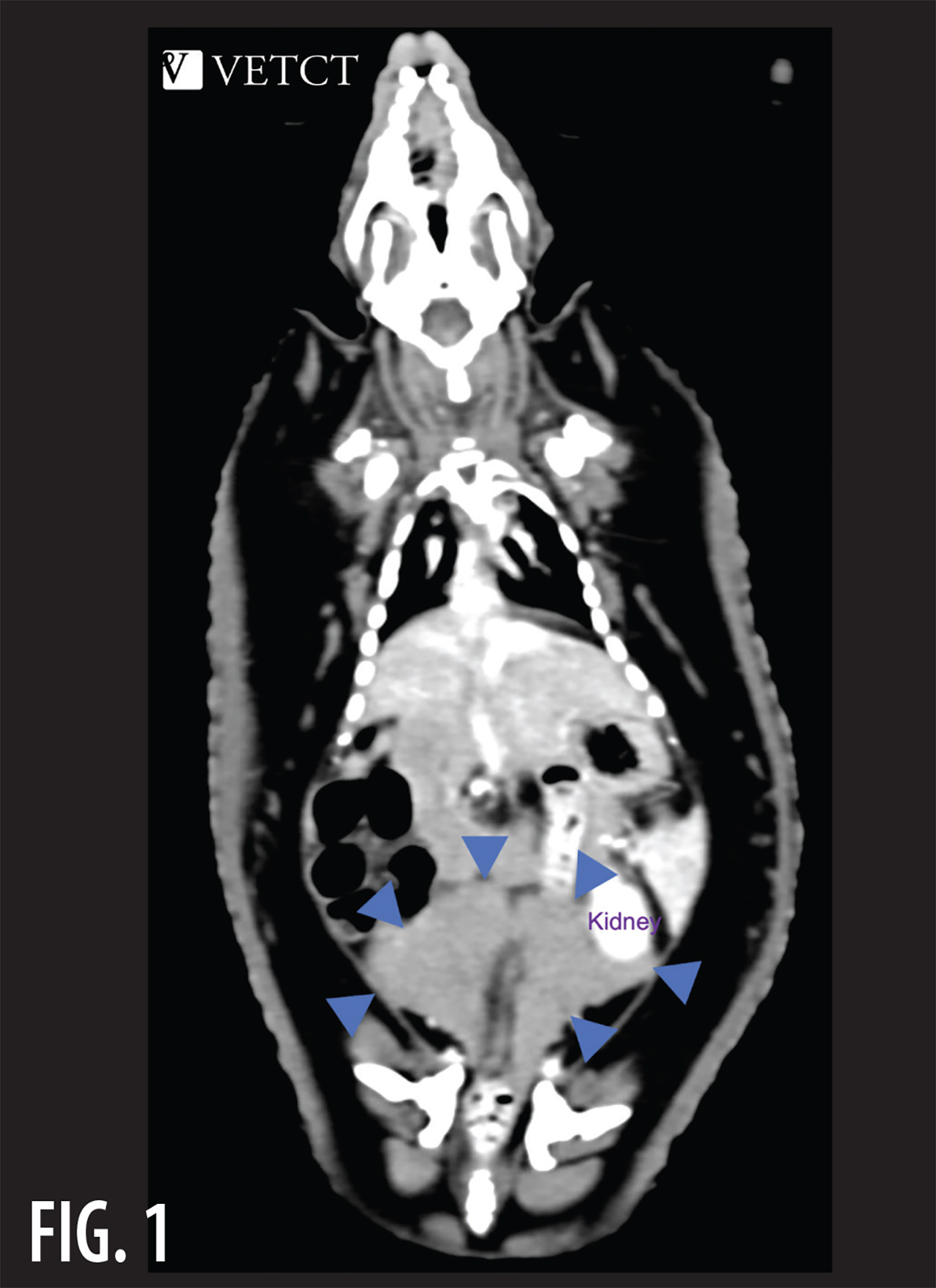

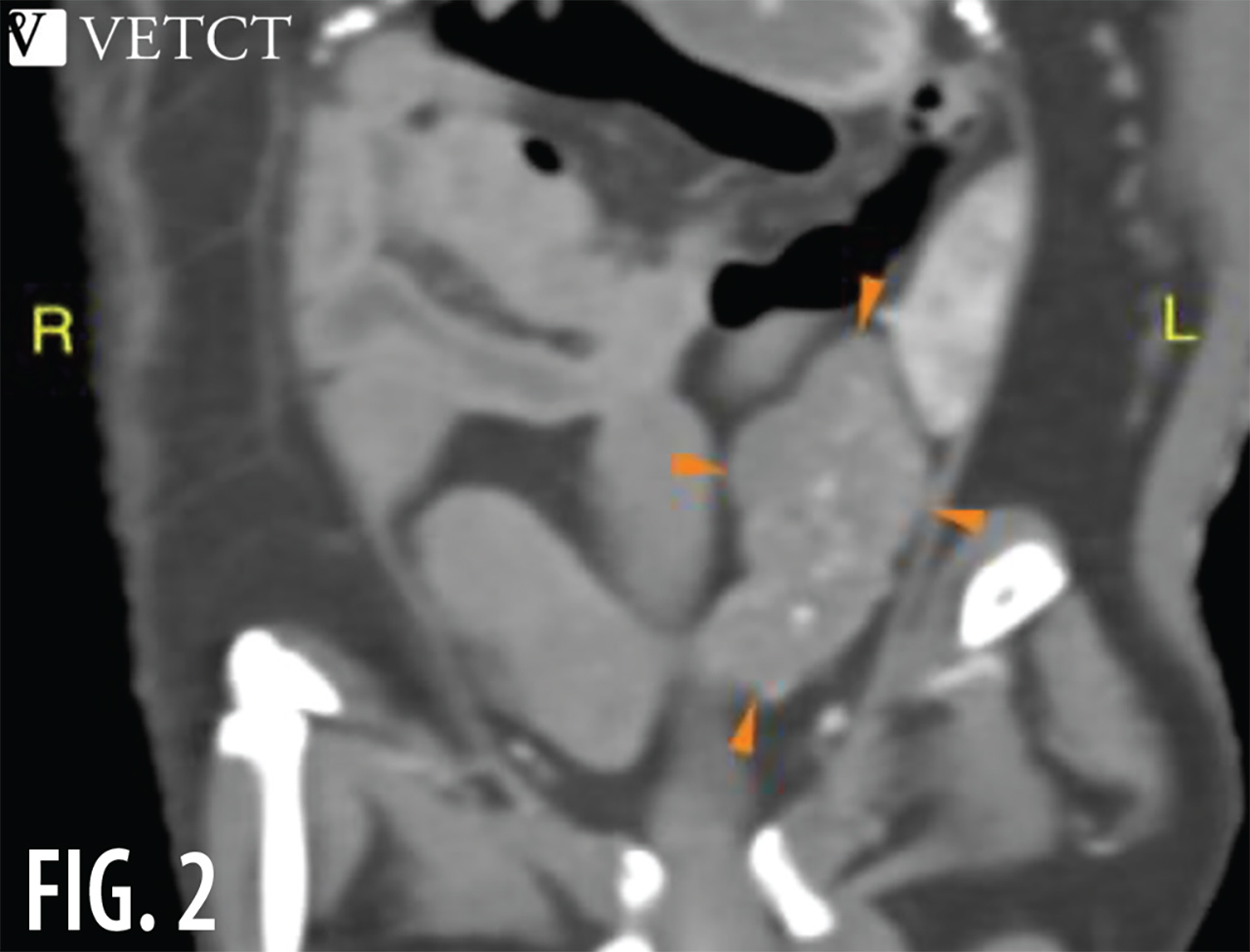

This is demonstrated in Fig. 1 of a suspected normal hedgehog and Fig. 2 of a suspected abnormal hedgehog CT with contrast enhancement. In the suspected normal CT image, the dorsomedial and ventrolateral lobes of the vesicular glands (blue arrows) are symmetrical with no mineralization. The hedgehog that is suspected to be abnormal (orange arrows) has asymmetry of the vesicular glands and visible mineralization of the left gland. The shape is different between the two images because of the overlapping dorsomedial and ventrolateral lobes of the vesicular glands in the normal animal. Without CT, we would not have been able to make an antemortem diagnosis for this hedgehog.

Consistent Across Species

Among our special species, previously unreported conditions are now identified with the help of contrast-enhanced CT. Understanding these conditions allows us to identify unexpected etiology and provide better care to our patients. Working with radiologists skilled in reviewing CT for exotic species has led to the rapid diagnosis and surgical correction of gastric dilatation and volvulus in rabbit, a previously unreported condition for the species.5 Among non-domestic species, this condition is often considered fatal because we were previously unable to diagnose and surgically correct it in time.6,7,8

It can be a challenge to coordinate a CT and image review rapidly enough for successful surgical correction for a condition like GDV. However, the increased availability of CT combined with the use of teleradiology allows us to rapidly access radiologists with exotics experience so that we can receive results directly no matter what time zone or time of day/night.

- Verhulst, C., Aitken‐Palmer, C., & Holliday, C. (2019). New Imaging Approaches Enable Visualization of 3D Musculoskeletal Anatomy of African White‐bellied Pangolin. The FASEB Journal, 33(S1), 613-8.

- Zoo and Aquarium Radiology Database (ZARD), an Innovative Imaging Database Designed to Support Wildlife and Zoo Professions, proceedings IAAAM 2022, Eric T. Hostnik1,2*; Michael J. Adkesson1; Matt Kinney3

- “Free online collection of veterinary diagnostic imaging cases and hematology images of zoo animals.” www.imaios.com/en/zoo-paedia

- McEntire, M. S., Ramsay, E. C., Price, J., & Cushing, A. C. (2020). The effects of procedure duration and atipamezole administration on hyperkalemia in tigers (Panthera tigris) and lions (Panthera leo) anesthetized with -2 agonists. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 51(3), 490-496.

- Imrie, P. (2022). Vets Need to Be Aware of Rabbit GDV. Vet Times. www.vettimes.co.uk/news/vets-need-to-be-aware-of-rabbit-gdv-danger/

- Hinton, J. D., Aitken-Palmer, C., Joyner, P. H., Ware, L., & Walsh, T. F. (2016). Fatal gastric dilation in two adult black-footed ferrets (Mustela nigripes). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 47(1), 367-369.

- DiGeronimo, P. M., Enright, C., Ziemssen, E., & Keller, D. (2023). Fatal gastric dilatation and volvulus in three captive juvenile Linnaeus’s two-toed sloths (Choloepus didactylus). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 54(1), 211-218.

- Hinton, J. D., Padilla, L. R., Joyner, P. H., Schnellbacher, R., Walsh, T. F., & Aitken-Palmer, C. (2017). Gastric dilatation volvulus in adult maned wolves (Chrysocyon brachyurus). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 48(2), 476-483.