info@barkleigh.com

(717) 691-3388

Editorial

rebecca@barkleigh.com

Advertising

james@barkleigh.com

DVM, DACVS-SA

Jenifer Chatfield

DVM, Dipl. ACZM, Dipl. ACVPM

CVT

DVM, DACVECC

-

STAFF

- Publisher

Barkleigh Productions, Inc. - President

Todd Shelly - Vice President

Gwen Shelly - Chief Operations Officer

Adam Lohr - Executive Editor

Rebecca Shipman - Art Director

Laura Pennington - Sr. Graphic Designer

Brandi Aurelio - Web Master

Luke Dumberth - Marketing Consultant

Allison Smith - Social Media Coordinator

Cassidy Ryman - Digital Media

Evan Gummo - Director of Marketing & Client Relations

James Severs - Administrative / Marketing Assistant

Karin Grottola - Graphic Designer

Carlee Kubistek

DVM, CVPM

s you begin your veterinary career, prioritizing financial planning is non-negotiable if you have plans to purchase or open a veterinary hospital. Establishing a solid financial foundation early on will allow you to open your practice with peace of mind, knowing your finances are in good shape.

Whether you are a first-year veterinary student, a recent graduate or have a newfound dream of hospital ownership, here are some areas to take into consideration as you prepare financially.

In addition, you’ll still be able to access financing for your hospital, even with student loans. Healthcare-specific underwriting teams understand that most veterinary students need student loans to complete their schooling. Therefore, student loans are usually labeled as “good” debt. Instead of looking solely at student loans, a lender will consider your personal credit, source of income, proof of financial responsibility and ability to accumulate savings.

It’s important to note that student loans should still be a factor in your financial planning. As you finish school or look into acquiring a practice, you should factor your student loans into your monthly budget and develop a plan for paying them off efficiently. They should always be a priority so you can avoid penalties and continue to build a positive credit history.

- Evaluate your monthly expenses. Identify your current spending habits by determining what items are essential and where you can cut costs. Do you need the $10 iced latte from the local coffee shop, or can you make a pot of coffee at home? Identifying any and all ways to cut costs will help you in the long run.

- Evaluate your debt priorities. What “bad” debt have you accumulated that you can pay off before applying for a loan? If you’re looking at credit cards, prioritize paying off those with a higher interest rate.

- Develop a timeline. It’s easy to say you want to pay off your debt or have a certain amount saved up by the time you apply for a loan, but what’s keeping you on track? Establishing a timeline with goals can help. Don’t forget to celebrate your achievements as you build wealth or improve your credit.

- Ask for help. If you’re struggling with budgeting, it’s okay to ask for help. Many financial advisors specialize in helping healthcare providers, and they can help you develop and stick to a plan.

- Use budgeting tools. In this day and age, there are many budgeting apps to help you stay on track and consistently monitor your spending. Some apps can even break down how much money you spend on shopping and eating out, allowing you to put things into perspective and identify cost-saving opportunities.

The path to veterinary hospital ownership can be intimidating, but it’s important to know that industry professionals can help you achieve your dream and walk you through each step, and there are various budgeting resources at your disposal. All it takes is proper planning and the drive to succeed. Before you know it, you’ll welcome your first patient and see your hard work pay off.

eterinary school taught me to be afraid of my career.” My heart sank when I heard those words from one of my coaching clients recently. In addition to the empathy and compassion I instantly felt for her for her, I was devastated for our profession as a whole.

For years I’ve suspected this was the case; that our academic veterinary programs have been inadvertently teaching future veterinarians to fear the profession they are working so hard to join. But my client’s unprompted words confirmed what I had concluded from interacting with thousands of veterinary professionals since 2017.

Veterinary school, and the traditional career environment that follows, create the perfect conditions to seed and nurture fear. However, we can’t blame veterinary education alone for this unintended consequence. It actually begins much earlier, during our first experiences as students…

Those enrolled in professional veterinary education are excellent students. They’ve spent most of their lives perfecting their academic performance and are the best of the best when it comes to academic intelligence—a trait that has been woven into their personal identity. Then, they enroll in veterinary school, and we crush them…

It starts with their very first exams, where many fail to land above 90%. This is devastating for a student who has a history of successful study habits and test performance. It’s confusing, too. From their perspective, they’ve done the work, they went to class, studied the materials, presented and assigned, and come test day, they were not prepared for what the exam included. How did this happen?

Herein lies the first problem…veterinary schools have admitted a population of students with a history of performing at the far-right end of the academic Bell Curve, and from that academically elite population, they must recreate a Bell Curve distribution of grades in order for their teaching approach to be considered successful. It’s kind of like taking a collection of yellow marbles and being required to turn that group into a collection that includes every color of the rainbow. It can probably be done, if we get really creative in our approach.

Similarly, the methods many use to achieve a Bell Curve from a population already known to be at the extreme right are often “creative.” Students are subjected to unanticipated testing methods and content detail beyond what was presented, assigned, and actually necessary to evaluate true information comprehension and retention.

The result? Many perform far worse on their first exams than they personally anticipated. This not only shakes their confidence, but it also disrupts their foundation of self-worth as fear of failure presents as a very real potential reality.

Academically, most rebound quickly, figuring out the rules of this new game. Those with aspirations of specializing become determined to win the game, often sacrificing their mental health and physical wellbeing to be perceived as performing well. They operate from a belief that it’s not enough to get good grades—you’ve got to be liked as well if you want to collect strong recommendation letters for the coveted internship spots. In this quest, they mold themselves into who they believe they should be in order to succeed, and lose their sense of individual identity in the process.

We warn them. We tell them to stay aware. We scare them to death. And we do this without equipping them with any knowledge or skills to navigate the stress and anxiety they will likely experience. We do not help them to normalize their experience, and so many secretly believe they are the only ones stressed out and suffering. They experience deep shame for the negative emotion they experience, especially when they believe everyone else is doing great. This quietly compounds the problem.

In addition, we encourage them to practice self-care without teaching them what that actually means, and without creating the space for them to actually do so. The unintended result? Emotional crisis that is hidden and attempted to be compensated for through academic success: “If I can get good grades, I must not be as bad as I secretly believe I am.”

In the real world, veterinarians unknowingly replace those academic scores with two things: 1) patients who get better and 2) clients who are happy. They replace practice of veterinary medicine with a new, unattainable expectation: the perfection of veterinary medicine. In addition, they interpret a fundamental tenet of the Veterinary Oath in a completely unintended way: “First, do no harm” becomes “If my patient shows the slightest evidence of discomfort, I’ve failed.” Unknowingly, they’ve created a scenario where failure becomes their only possible destination.

Meanwhile, they are literally fearing for their lives. Every moment of discomfort, every bad outcome, every ugly client interaction…they all become relatable justification for why veterinarians take their own lives. And we’ve taught them to watch for it, as if they don’t have choice. Add to that their mountain of student loan debt and the belief that staying trapped in a profession where they are failing is the only way to repay it, and suicide becomes a viable exit strategy.

So, where do we go from here?

Truth #1: Our value and self-worth are never contingent upon anything outside of ourselves; they are absolutes simply because we exist. They can’t be created, they can’t be destroyed, and they are absolutely never dependent on any experience in veterinary medicine.

Truth #2: Negative emotional experiences are not evidence of failure or indicators that circumstances exist that need to be fixed. All emotions, including negative emotions, are natural human experiences and created only by internal thought patterns including our own opinions, beliefs and conclusions. Our emotional wellbeing, therefore, is never dependent on patient outcomes, client behavior or anything outside of ourselves.

Truth #3: Learning to leverage the space is the single most effective way to decrease stress and anxiety and expand personal wellbeing, no matter what happens at work or in the world. You are the creator of your own reality. You are powerful. You don’t need external validation to believe in yourself.

We have an opportunity to get in front of the mental health crisis that has become the acceptable norm in veterinary medicine. The bright future we dream of is within our reach. It is our responsibility to create it not only for ourselves, but for all of those who are yet to come. It’s time break the cycle!

t seems like everything is “smart” these days…your refrigerator can tell you when you’re out of milk, your thermostat can adjust to your favorite temperature and your car can nearly drive itself. Artificial intelligence is even creeping into the veterinary world. But before we get carried away and give AI complete control, let’s take a moment to reflect on why, just maybe, pet care businesses aren’t quite ready to trust an AI model with their marketing needs.

Firstly, AI cannot appreciate a clever joke, and what’s pet care marketing without some good old-fashioned canine humor? Sure, it can theoretically generate a joke based on complex algorithms and data patterns, but will it truly understand why a dog crossing the road is funny? To AI, that dog is just a variable, running risk assessments for incoming traffic.

And let’s not forget about those consultation calls. Imagine your customer, a proud Poodle mom, getting advice from AI: “Your pet has a 37.2% probability of having a diet-related problem based on current data input.” With all due respect to our robotic friends, that’s hardly a comforting or personalized response. AI doesn’t know that the Poodle has a penchant for filching roast beef from the Sunday dinner table.

On to the technological aspect…Yes, AI can analyze data faster than a Greyhound chasing a rabbit. It can churn out email campaigns, social media posts and even blog content while you’re still fumbling with your morning coffee. But AI doesn’t understand the emotional bond between humans and their pets. It can’t tell a heartwarming story about a cat, Mr. Whiskers, who kept pawing at his owner’s chest and saved her life by detecting early-stage breast cancer. AI also can’t empathize with the traumatic experience of Mrs. Johnson when her beloved parrot, Chirpy, flew out of the window. Imagine AI attempting to send an uplifting message: “Dear Mrs. Johnson, we hope you are 87% less distressed about Chirpy’s adventure.” Talk about a mood killer!

It also doesn’t know what it hasn’t learned yet. When it comes to product marketing, AI is excellent at remembering what products were bought and how often. For example, your client will receive an email when it’s time to reorder Spot’s flea and tick medication, but AI doesn’t know that Spot was tragically hit by a car last week. While AI’s message might be timely, it doesn’t account for the recent trauma experienced by Spot’s owners.

Or consider the case of blog writing. AI can quickly generate a 500-word article on the benefits of neutering, complete with statistics, but it lacks the narrative flair that keeps readers engaged. A seasoned veterinary writer might weave in a charming tale of Mr. Jingles, a once feisty tomcat who, after his neutering, gave up his wandering ways to embrace the peaceful home life, thereby encouraging pet owners more effectively.

On a more serious note, when it comes to medical advice, AI hasn’t quite mastered the nuances. It might direct an owner to apply salve on a Husky’s hot spot, but it won’t understand if the husky, named Zeus, is a bit of a drama king and might need a more delicate approach. And what if AI recommends a diet change for a stubborn feline who would rather fight the vacuum cleaner than give up her favorite salmon treats? Cue AI sending an email reminder: “Your cat may experience a 32.5% weight reduction.” Meanwhile, the cat in question has already decided to go on a hunger strike.

In conclusion, while AI’s speed, data handling and 24/7 availability make it a tempting prospect for pet care marketing, it still has a long way to go before it can compete with the warmth, humor and individual understanding that humans bring to the table. From the inability to tell a truly humorous joke to the failure in empathizing with pet parents, AI falls short of the standards set by human intuition and interaction.

For the foreseeable future, the critical tasks of catering to distressed pet parents, creating engaging narratives and establishing genuine relationships will remain in the capable hands of humans. After all, it takes a pet lover to truly understand another pet lover—and that’s something AI, in all its binary glory, just can’t replicate yet.

hose of us that care for unique species rely on every diagnostic tool in existence, and even then, we still have to get creative for our patients. For many of our species, we do not have a known normal for comparison or reported reference ranges to rely on. Even as a Board-Certified Specialist in Zoological MedicineTM, this can feel like a limitation to the care I can provide to my patients. The species we care for vary widely. In a single day, a veterinarian caring for non-domestic species might examine a rabbit, a bearded dragon, a blue and gold macaw, and an echidna. Each has vastly different physiology, anatomy and disease prediction.

Detailed Anatomy

Computed Tomography with contrast enhancement has opened a new chapter to understand the anatomy of these species antemortem.1 Searchable databases are currently under development. Once we know the normal anatomy, it helps us better recognize abnormal disease changes when they occur.2,3

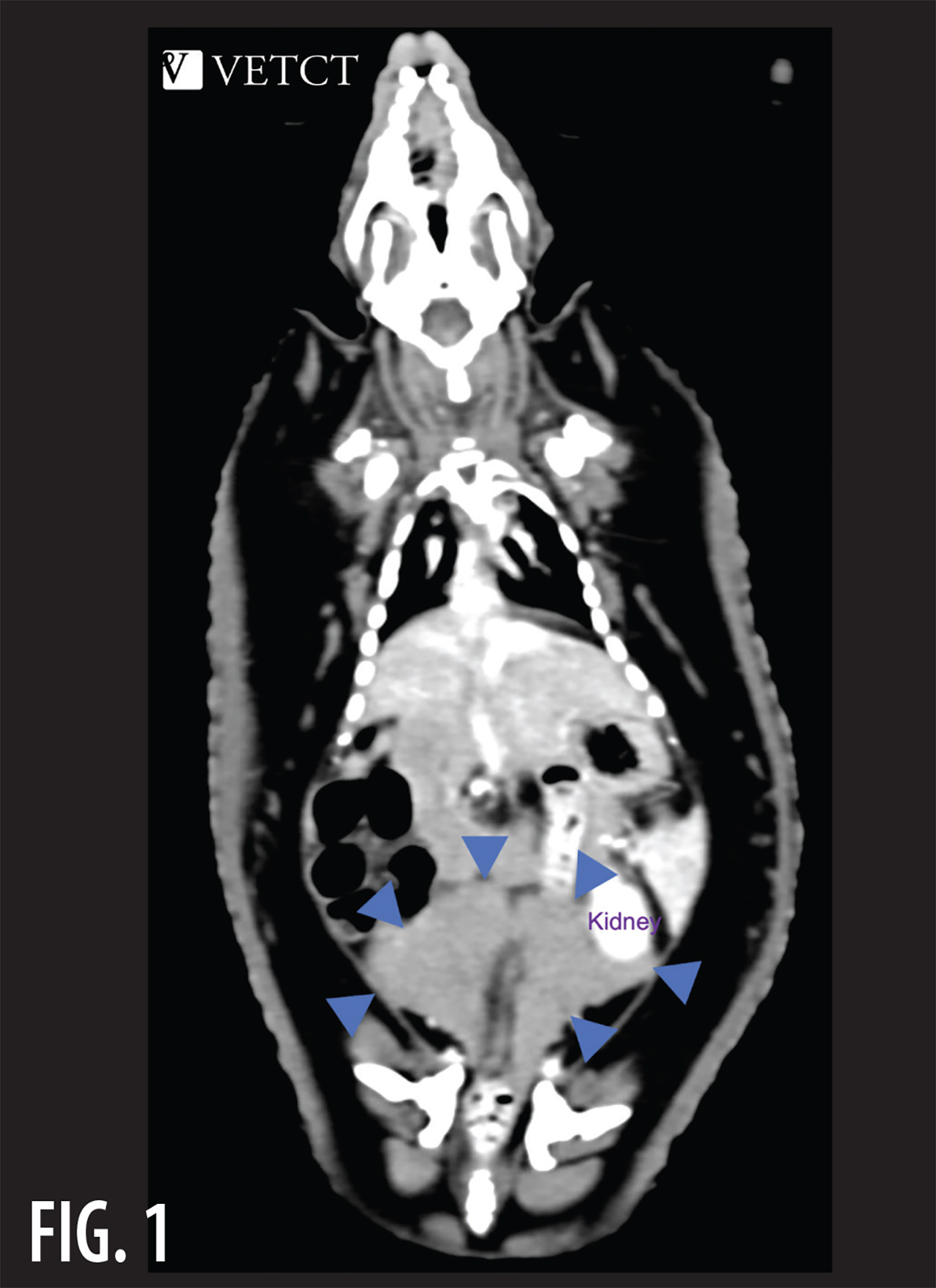

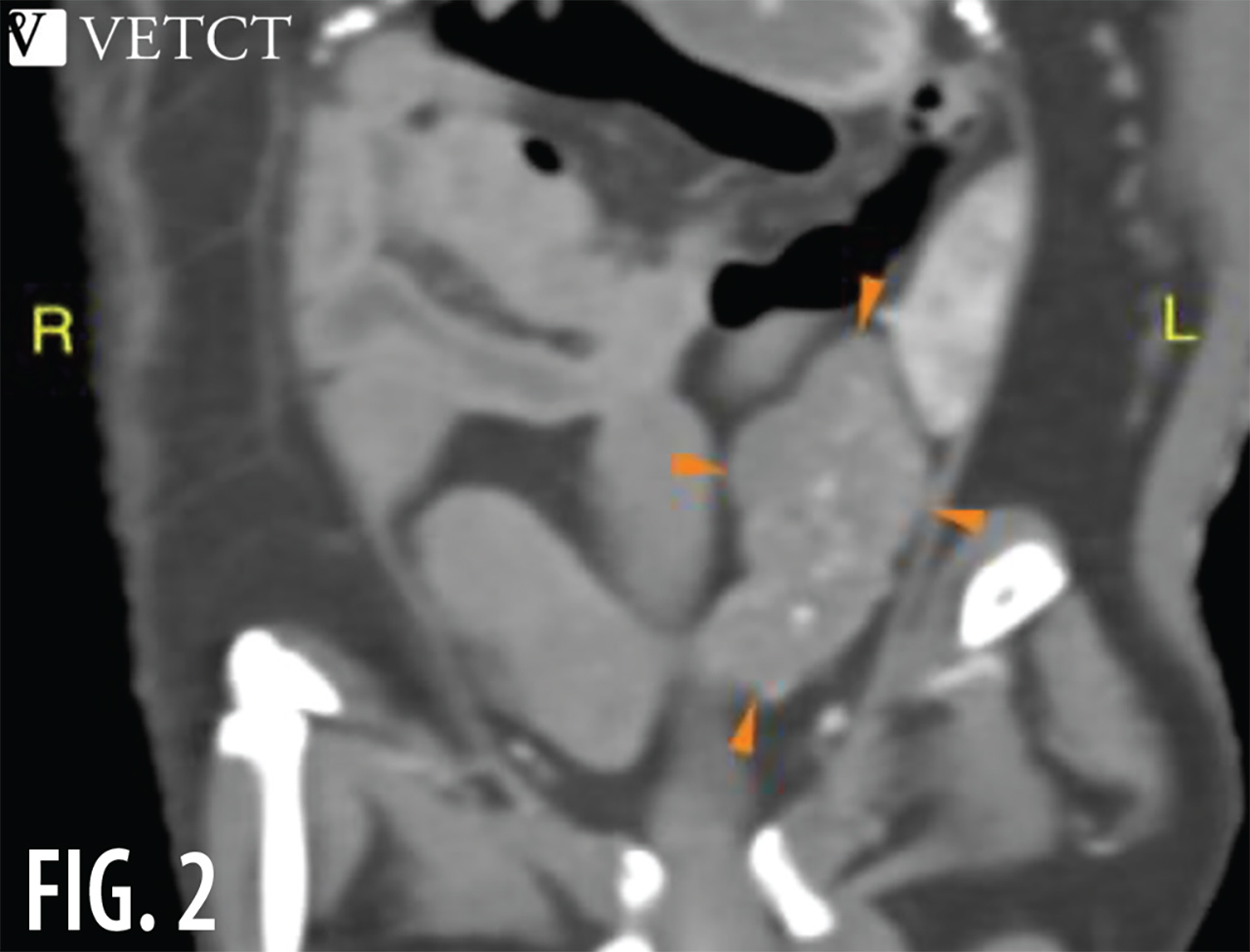

This is demonstrated in Fig. 1 of a suspected normal hedgehog and Fig. 2 of a suspected abnormal hedgehog CT with contrast enhancement. In the suspected normal CT image, the dorsomedial and ventrolateral lobes of the vesicular glands (blue arrows) are symmetrical with no mineralization. The hedgehog that is suspected to be abnormal (orange arrows) has asymmetry of the vesicular glands and visible mineralization of the left gland. The shape is different between the two images because of the overlapping dorsomedial and ventrolateral lobes of the vesicular glands in the normal animal. Without CT, we would not have been able to make an antemortem diagnosis for this hedgehog.

Consistent Across Species

Among our special species, previously unreported conditions are now identified with the help of contrast-enhanced CT. Understanding these conditions allows us to identify unexpected etiology and provide better care to our patients. Working with radiologists skilled in reviewing CT for exotic species has led to the rapid diagnosis and surgical correction of gastric dilatation and volvulus in rabbit, a previously unreported condition for the species.5 Among non-domestic species, this condition is often considered fatal because we were previously unable to diagnose and surgically correct it in time.6,7,8

It can be a challenge to coordinate a CT and image review rapidly enough for successful surgical correction for a condition like GDV. However, the increased availability of CT combined with the use of teleradiology allows us to rapidly access radiologists with exotics experience so that we can receive results directly no matter what time zone or time of day/night.

- Verhulst, C., Aitken‐Palmer, C., & Holliday, C. (2019). New Imaging Approaches Enable Visualization of 3D Musculoskeletal Anatomy of African White‐bellied Pangolin. The FASEB Journal, 33(S1), 613-8.

- Zoo and Aquarium Radiology Database (ZARD), an Innovative Imaging Database Designed to Support Wildlife and Zoo Professions, proceedings IAAAM 2022, Eric T. Hostnik1,2*; Michael J. Adkesson1; Matt Kinney3

- “Free online collection of veterinary diagnostic imaging cases and hematology images of zoo animals.” www.imaios.com/en/zoo-paedia

- McEntire, M. S., Ramsay, E. C., Price, J., & Cushing, A. C. (2020). The effects of procedure duration and atipamezole administration on hyperkalemia in tigers (Panthera tigris) and lions (Panthera leo) anesthetized with -2 agonists. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 51(3), 490-496.

- Imrie, P. (2022). Vets Need to Be Aware of Rabbit GDV. Vet Times. www.vettimes.co.uk/news/vets-need-to-be-aware-of-rabbit-gdv-danger/

- Hinton, J. D., Aitken-Palmer, C., Joyner, P. H., Ware, L., & Walsh, T. F. (2016). Fatal gastric dilation in two adult black-footed ferrets (Mustela nigripes). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 47(1), 367-369.

- DiGeronimo, P. M., Enright, C., Ziemssen, E., & Keller, D. (2023). Fatal gastric dilatation and volvulus in three captive juvenile Linnaeus’s two-toed sloths (Choloepus didactylus). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 54(1), 211-218.

- Hinton, J. D., Padilla, L. R., Joyner, P. H., Schnellbacher, R., Walsh, T. F., & Aitken-Palmer, C. (2017). Gastric dilatation volvulus in adult maned wolves (Chrysocyon brachyurus). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 48(2), 476-483.

By Louise Dunn

or many of us, “stress” has become a common term tossed around with a flippant remark or a threatening stare. You most likely have blamed stress when explaining why you failed to complete a task: “Things are really stressful today; I’ve barely had time to breathe.” Or, perhaps after you snapped at a co-worker: “Don’t mind me, I’m stressed out.”

As often as we use the word during our day, have we ever taken the time to understand stress and its effects on our mental health, the team, and our family and friends at home? Just what is stress, and how can we relinquish its hold on our daily activities?

At this point, you may be thinking that since stress is a personal state of mind, the business has no “business” in the employee’s mind; however, this is where the stance to “leave your problems at the door when you come to work” comes into play. You have most likely said this phrase or been on the receiving end. The truth is, the business should pay attention to team members’ stress, regardless of its source.

Stress can also have a ripple effect. Not only is Sue stressed, but now her manager is stressing about speaking to Sue. The team is whispering about how worried they are about Martha, adding stress to their own lives. In addition, everyone is wondering what is wrong with Jack because they are tired of picking up his slack which is causing them stress. Stress was not left at the door when they walked in to work that day. Stress came with them, and it affected everyone else on the team.

Dr. David Posen, author of Is Work Killing You?: A Doctor’s Prescription for Treating Workplace Stress, placed workplace stress into three categories: Velocity, Volume, and Abuse.3 These three categories are readily apparent in the workplace of pet professionals. Here is how they are defined:

- Velocity. Everything seems to happen at the speed of light, or at least at the speed of the internet these days. Clients want access to you and the team ASAP—be it by phone call, text message or appointment. And team members want tasks done as of yesterday.

- Volume. Appointment requests outnumber openings available. Pet professionals are busy, and the sheer volume of work can result in long hours and skipped meals.

- Abuse. The third category is one we often tend to be silent about. It is about abuse, harassment, intimidation, bullying, belittling and threats. Work is not all playful kittens and puppy kisses. It can be snide remarks from a co-worker about your incompetence, intimidation from a client accusing you of only wanting the money and not caring about the pet, threats about being fired if you don’t move faster or jump higher, or harassment from those difficult personalities.

At this point, you may think that stress simply comes with the territory. However, while it may be true that the practice will likely continue to operate with volume, velocity and abuse, it is not true that its team members can’t be helped in dealing with the stress.

- Implement organizational changes to reduce employee stress. Clearly define roles (job descriptions) and responsibilities (SOPs). Create a quiet area for meals and breaks and schedule them so they aren’t missed.

- Ensure that mental health services are part of the organization’s health benefits and encourage the team to utilize the services.

- Provide education and training on dealing with stress. Use resource materials from the insurance provider at monthly meetings to discuss stress and other mental health concerns.

- Consider having an Employee Assistance Program (EAP). EAPs offer intervention programs to assist employees in resolving problems by offering services for counseling, substance abuse, stress, grief, family problems, crisis intervention, workplace coaching and basic legal assistance. EAPs are voluntary and confidential.

The goal of your programs and plans is to improve the mental and emotional wellbeing of the individual. But how do you reach an individual needing assistance? First, you may need to change the company culture…

- Always focusing on what is wrong.

- Criticizing or punishing people for taking time off.

- Giving negative feedback instead of praise or positive feedback.

- High turnover of team members.

- High absenteeism.

- Low productivity.

- Abusive management or leaders.

- Lack of leadership or an overly dominating leader.

If you check any of these off, you may have a toxic culture. Instead, you want to have a culture that emphasizes productivity and connectedness. A connected culture has a shared identity and an understanding of the vision. A connected culture values everyone on the team and provides the opportunity to voice ideas and opinions.1

Factors that are part of a connected culture are:

- Celebrating core values.

- Understanding priorities.

- Understanding the vision and being inspired to achieve goals.

- Everyone knows where they are going and how they are getting there.

- Non-leaders are encouraged to grow and thrive.

- Team members are in the right seat on the bus.

- People are challenged to enhance their skills and knowledge.

- Team is supportive of each other.

- Constructive feedback is given.

- It is psychologically safe to share ideas, give opinions, and even disagree.

Creating this cultural shift can seem daunting; after all, change is a stressor. An easy starting point is showing you care by simply asking. However, do not ask, “What’s wrong with you?” and then tick off a list of advice for the individual. It is equally harmful to ask, “Are you depressed?” because you are venturing into disability claims under the Americans with Disabilities Act. Instead, focus on behaviors and performance.

Consider stating, “I notice you don’t seem like yourself,” or “I am concerned about you.” When talking about performance issues, you can say, “You are usually very thorough, but now you are missing things. Is there something going on that we can support you with?” This sounds much better than, “Man, what’s wrong with you? You need to get your act together.”

Once you ask though, you need to take action. Do not ignore issues. This is the time to point out resources like health insurance coverage, the EAP, or even short-term disability benefits. The business needs a culture that encourages team members to recognize distressed co-workers and respond accordingly.

A business can no longer demand that employees leave their problems at the door when they come to work. The business needs to have a strategic plan to address its team members’ mental and emotional wellbeing to allow individuals to reach their full potential, cope with stressors, be productive, and deliver high-quality client service and pet care.

- Stallard, M.L., Stallard, K. (2014, Jan). Combating Workplace Stress. SHRM.

- Ray, A. (2011, Dec). To Promote Wellness, Help Employees Reduce Workplace Stress. SHRM. https://www.shrm.org/ResourcesAndTools/hr-topics/benefits/Pages/ReduceStress.aspx

- Owens, D. (2014, Mar). Dr. David Posen’s Prescription for Work Stress. SHRM. https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-magazine/pages/0314-workplace-stress.aspx

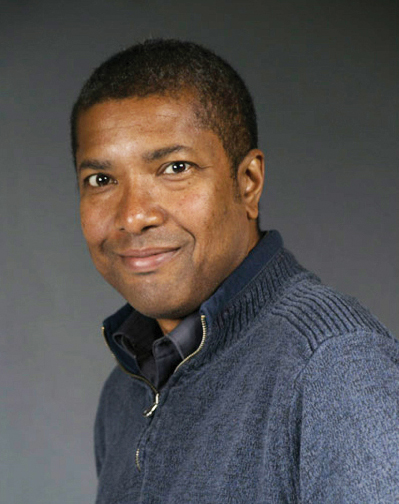

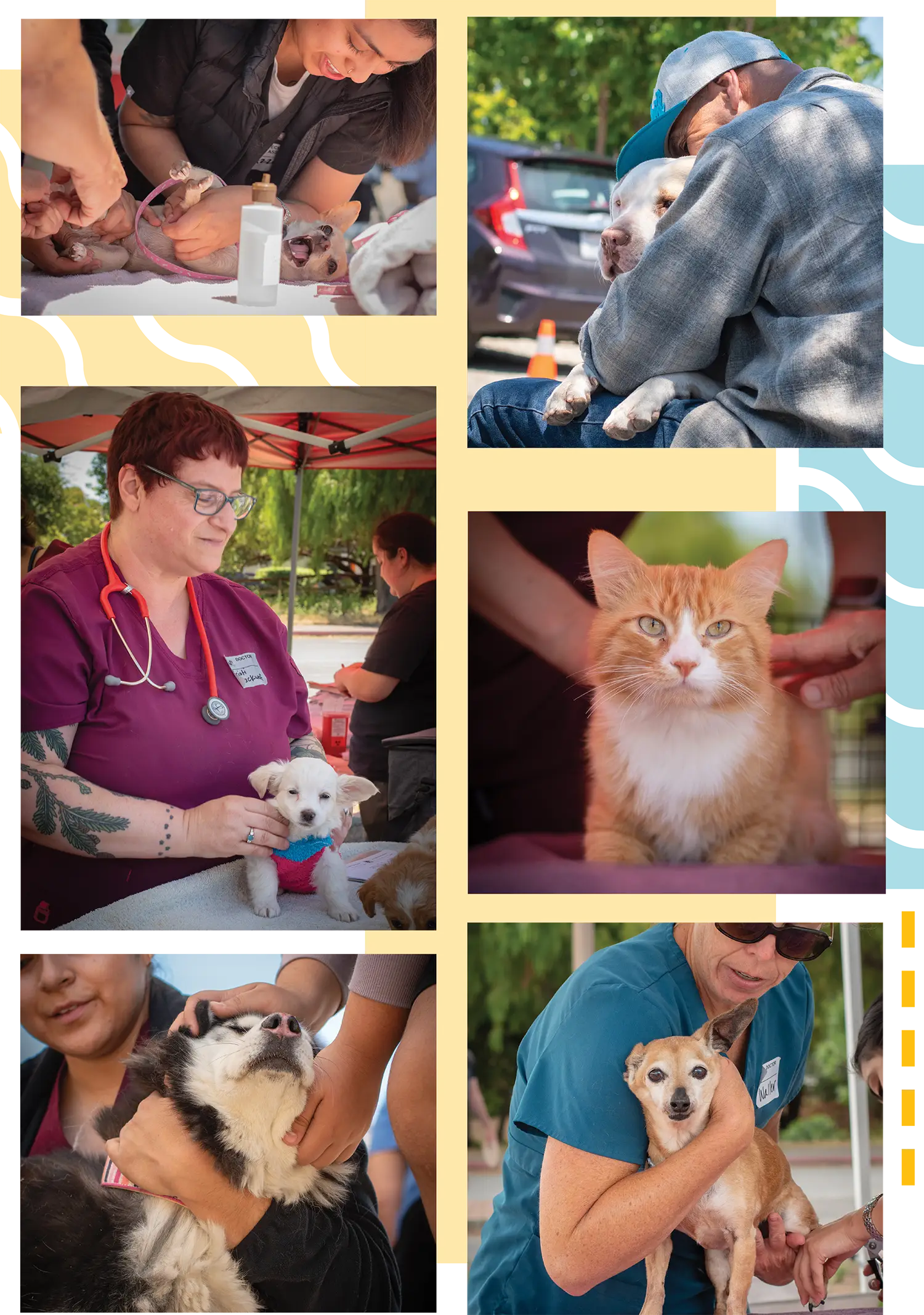

Photos provided by The Street Dog Coalition

ewey is my ultimate advocate. He means everything to me and I make sure he’s taken care of. If he’s warm and happy, then I’m warm and happy,” shares Cody, a young man experiencing homelessness in Colorado who has received services for his dog, Dewey, from The Street Dog Coalition.

The Street Dog Coalition (SDC) is an international nonprofit founded in Fort Collins, CO in 2015, which now has over sixty teams across the country and in Ukraine, providing free medical care and related services to pets of people experiencing, or at risk of, homelessness. Entirely volunteer driven, SDC cares for both the pet and the person at their far-reaching pop-up street clinics.

Living a nomadic life on the street is an informed decision made by some, but for many, it is not a choice. Living on the street can be dangerous, lonely and taxing—socially, emotionally and physically—especially when there is little to no access to care. Understandably, people experiencing homelessness with companion animals describe their pets as a source of unconditional love, comfort, safety, support, motivation to reduce substance use, and even to continue living.

That said, unhoused individuals should not have to make the impossible decision between having a roof over their head or staying with their beloved pet. This is why The Street Dog Coalition is endorsing the Providing for Unhoused People with Pets (PUPP) Act. If passed, the bill will establish a grant program administered by USDA. Funds will help local governments and nonprofit organizations that provide shelter or permanent supportive housing to retrofit property to accommodate unhoused individuals with pets, while also providing additional veterinary services, including spaying and neutering, vaccinations and other basic medical procedures.

If you’re interested in being a part of The Street Dog Coalition by volunteering, donating and/or advocating for both ends of the leash, please visit their website, www.thestreetdogcoalition.org

These guidelines provide insights and strategies for implementing mentorship programs that address the pressing need to improve recruitment, retention, job satisfaction, and diversity within veterinary practices. aaha.org

2 leading trade magazines for the pet professional in your life with all the content to assist them in keeping your pet healthy, happy and beautiful.

online or in print at www.barkleigh.com

Facebook.com/

barkleigh.prod

Twitter:

@barkleighinc