Inquiries

info@barkleigh.com

(717) 691-3388

Editorial

rebecca@barkleigh.com

Advertising

james@barkleigh.com

- AnimalsINK7

- Barkleigh Show Schedule35

- Barkleigh Store – Boarding Kennels: The Design Process29

- Barkleigh Store – Groom Curriculum21

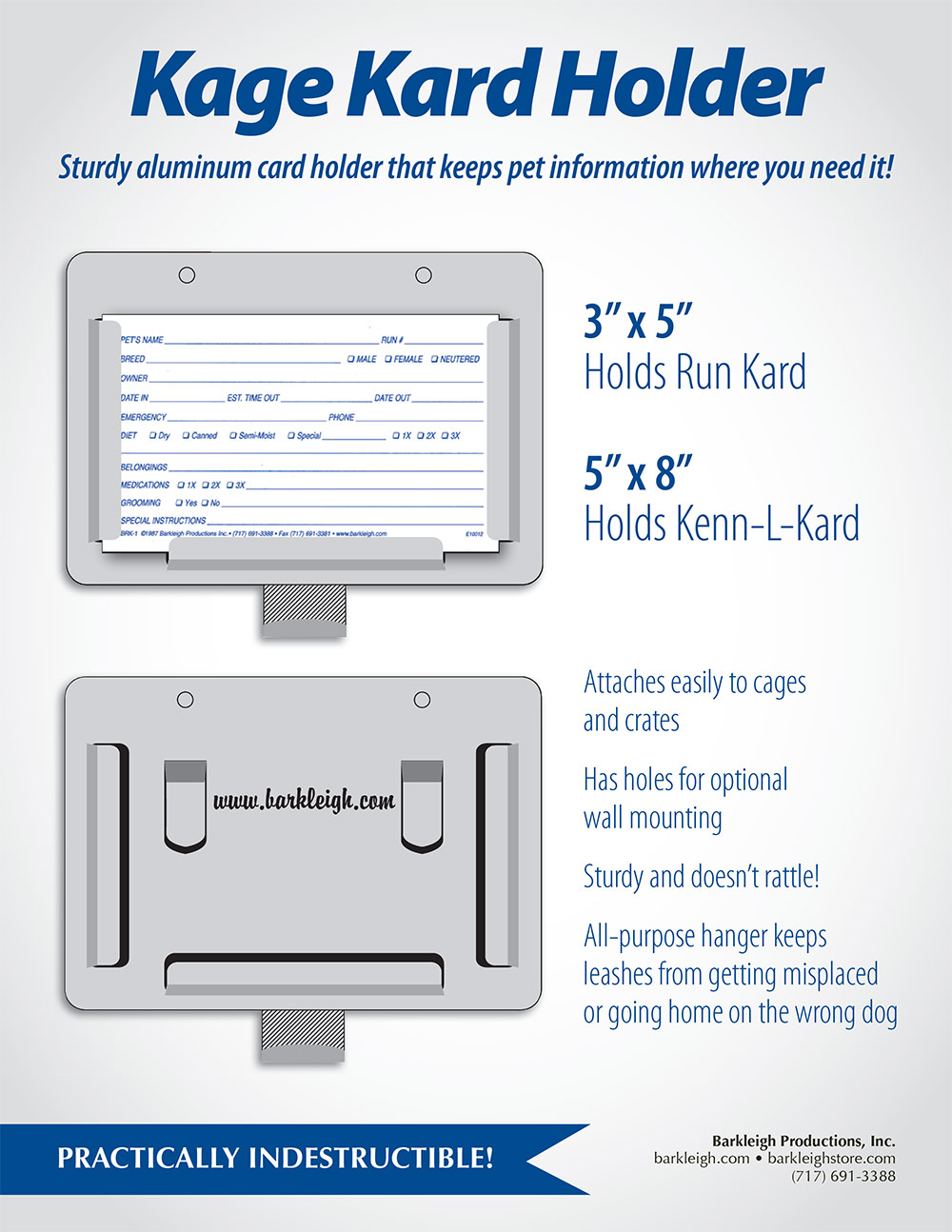

- Barkleigh Store – Kage Kard Holder15

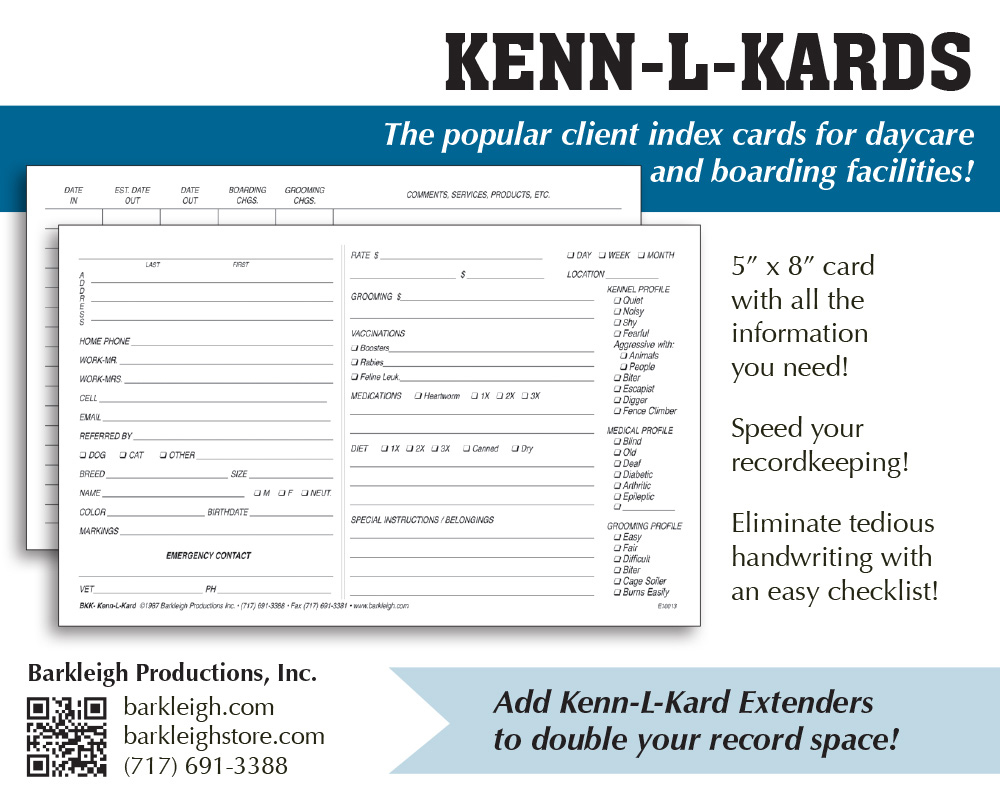

- Barkleigh Store – Kenn-L-Kards17

- Barkleigh Store – The Pet Stylist Playbook25

- Barkleigh Store – The Rosetta Bone11

- CashDiscountProgram.com5

- CleanWise23

- Gator Kennels12

- Gyms for Dogs16

- Odorcide9

- Pet Boarding and Daycare Expo36

- PetLift13

- Wag’n Tails2

Gateway

Ansell

Meet our EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD!

DVM, DACVS-SA

Jenifer Chatfield

DVM, Dipl. ACZM, Dipl. ACVPM

CVT

DVM, DACVECC

-

STAFF

- Publisher

Barkleigh Productions, Inc. - President

Todd Shelly - Vice President

Gwen Shelly - Chief Operations Officer

Adam Lohr - Executive Editor

Rebecca Shipman - Art Director

Laura Pennington - Sr. Graphic Designer

Brandi Aurelio - Graphic Designer

Carlee Kubistek - Web Master

Luke Dumberth - Marketing Consultant

Allison Smith - Digital Media

Evan Gummo - Director of Marketing & Client Relations

James Severs - Accounts Manager/ Executive Assistant

Karin Grottola - Administrative Assistant

Britany Smith

DVM, CVPM

How to Retain Clients and Increase Revenue

By William Ormston, DVM

eterinarians enter the profession with a passion for healing animals—not necessarily a love of business. But in today’s increasingly competitive pet care landscape, smart practice management is essential to long-term success.

Practices that thrive do so not only because they provide excellent care, but because they evolve—offering services that meet modern client expectations, deepen patient relationships and support sustainable growth. And chiropractic care does all three.

Chiropractic is a natural fit for forward-thinking veterinary practices, offering clinical value as well as business benefit. The following will cover how adding animal chiropractic can improve your bottom line, boost client loyalty and set your practice apart in a crowded market.

Veterinary clients increasingly seek integrative options for their pets. They want more than medications and diagnostics—they want wellness, prevention and whole-body care. Chiropractic answers this demand. For the veterinarian, it represents a way to provide more complete care to existing patients without needing to increase staff, expand the facility or rely on expensive tools.

When framed properly, chiropractic doesn’t replace traditional care, it augments it. Whether it’s supporting a post-op patient, managing chronic mobility issues or improving the health span of a senior dog, chiropractic can become a core service in your practice, not just a fringe offering.

For example, let’s say 50 of your patients receive chiropractic care every six weeks at $75 per session. That generates roughly $3,750/month or $45,000/year—without adding inventory or extending hours.

Many clients are willing to pay out of pocket for chiropractic, as it’s seen as a premium service with direct quality-of-life impact. Even better, these clients are some of your most engaged and loyal; they show up for regular visits, comply with treatment plans and often refer others.

When a pet receives an adjustment and walks out moving better, clients can see and feel the difference. It creates immediate, observable value and deepens their trust. They begin to understand the body in new ways, ask questions and take ownership of their animal’s musculoskeletal health.

Clients feel seen and heard, especially when chiropractic helps with problems that haven’t responded to traditional treatment. This means they’re more likely to stay with your practice and refer friends who also value holistic or integrative care.

Offering chiropractic tells your community:

- We care about whole-body function, not just symptoms.

- We believe in proactive and preventative care.

- We offer modern, integrative solutions.

- We’re constantly learning and expanding to better serve you.

This reputation is powerful. Even if only a portion of your clientele uses chiropractic services, your practice becomes known as the place for advanced, thoughtful and complete care.

These success stories become your best marketing. Pet owners love to share when they’ve found something that truly helps their animal. A client whose dog was facing lifelong meds and sees improvement after chiropractic care is going to tell everyone—at the dog park, the groomer, the trainer and online.

Organic referrals from happy clients build your practice in a way no advertising campaign can replicate. And because chiropractic patients tend to require ongoing care, those referrals turn into long-term clients with higher lifetime value.

Once trained, you can immediately begin offering adjustments. The only tools you need are your hands and a quiet space. There’s no consumable inventory, no prescription costs and no third-party supplier markup. That means your margin on each chiropractic visit is extremely high, often 80% or more.

Many doctors have tripled their money in the first year of adjusting animals. When you compare that to surgeries or pharmaceutical sales, which involve significant materials, staff time and liability, chiropractic is a clean, efficient revenue stream that also supports your broader clinical goals.

Alternatively, you can bring in a certified chiropractor (either a DVM or DC) to see patients in your clinic on a part-time basis. This hybrid model allows your practice to offer chiropractic services without requiring you to complete the training yourself—while still capturing a share of the revenue and increasing client retention.

In short, offering chiropractic doesn’t require you to do it all. It just requires you to recognize its value and find the right model for your practice.

By incorporating chiropractic, you meet this growing demand before it pushes clients elsewhere. You position yourself not just as a traditional vet, but as a whole-health provider—one who embraces new modalities and leads with curiosity, not skepticism.

Even offering an initial conversation about chiropractic can set you apart: “Would you like us to assess your dog’s spinal mobility during their next exam? It’s a drug-free way to help with stiffness, gait changes, or aging-related issues.” It’s not a hard sell—it’s a clinical service rooted in patient wellness. And most pet parents say yes.

Chiropractic care isn’t just good medicine, it’s good business. It brings clinical depth, enhances patient outcomes, and keeps clients engaged and loyal. It adds recurring revenue, strengthens your brand and helps your practice stand out in a wellness-focused world. Most importantly, it helps animals feel better, move better and live longer—something every veterinarian wants.

By adding chiropractic, you’re not just expanding your service list, you’re investing in the future of your practice and the well-being of the patients you serve. The numbers add up, the results speak volumes and the opportunity is yours.

Helping Clients make Healthier

Choices for THEIR Dogs

By Melissa Viera

e’s the most food-motivated dog I’ve ever had,” the client says—and the scale confirms what’s easy to see: another overweight dog…

While it’s impossible to know how a client will react, when a dog is either obese or headed in that direction, it’s essential to help pet owners understand what a healthy weight looks like for their dog. To encourage clients to make better choices, veterinarians can evaluate feeding, training and snack routines.

When she talks with her clients about making changes, Dr. Pietsch explains how she feeds her dog, acknowledging that it’s not always easy to ignore begging.

“I talk about measuring the food volume with a measuring cup and discuss changing high-calorie treats or people food for low-calorie fruits and vegetables,” she says. “I review the calorie requirements of their pet, and then give examples of how many calories are in common treats or food.

“This really puts how many calories they are overfeeding into perspective,” Dr. Pietsch continues. “Finally, I acknowledge that weight loss is hard and that even small changes can help; slow and steady is the key.”

“As a veterinary surgeon, I’ve witnessed firsthand the unintended consequences of well‑meaning pet parents using too many training treats,” shares Dr. Courtney A. Campbell, DVM, DACVS-SA and founder of Stitches Veterinary Surgery in Long Beach, California.

Dr. Campbell recalls a case where a Labrador Retriever’s recovery from surgery was complicated due to obesity, which he traced to the family’s frequent use of training treats.

“A handful of treats here and there can quickly exceed 10–20% of a dog’s daily caloric needs,” he explains. “I often tell the story of my friend’s dog, Cody, who learned to ‘sit’ in a weekend but also gained a pound because he didn’t adjust his regular meals to account for the extra treats.”

Dr. Campbell suggests reading labels, feeding smaller treats and using regular kibble for training.

“I remind clients that praise, play, and affection can be powerful motivators,” he adds.

When it comes to client education, Dr. Campbell expresses that veterinary technicians play a key role: “Empower them to lead these discussions and provide ongoing coaching,” he suggests.

Courtney J. Sepeck is a veterinary technician, breeder and competitive dog exhibitor from Massachusetts who understands the importance of monitoring training treats when working with her dogs.

“Using their own food [in training] can help make sure the pet is not overfed,” explains Courtney.

While high-value treats are essential for training, she says that it’s crucial to pay attention to the number of treats that are used and how they are used in training.

Conversations that go beyond what dogs eat to why owners make the feeding choices they do can offer valuable insights and help veterinary professionals better support their clients.

Not only does Courtney discuss what a healthy weight looks like, but she also shows clients what it should feel like on their dog, taking into consideration how different breeds carry weight differently.

Another reason people overfeed their dogs has to do with the dog’s behavior. Some dogs seem to act hungry all the time, either devouring their meals, begging for treats or always on the lookout for something to eat. When owners call a trainer about dogs like this, it’s often because the dog is jumping up on countertops to steal food or their hunger has become a problem in other ways.

One study published identified a deletion in the POMC (pro-opiomelanocortin) gene present in some Labradors, which is linked to increased food motivation and weight gain.1 The POMC deletion affects appetite by disrupting normal satiety signals.

More recently, a genome-wide association study (GWAS) pinpointed the gene DENND1B as a strong obesity-associated variant in Labradors, which also plays a role in human obesity.2 The DENND1B regulates the activity of the melanocortin 4 receptor, which plays a major role in energy homeostasis.

Some suggestions that Dr. Campbell gives to clients who are concerned about their dog acting hungry involve preventing boredom and feeding an appropriate diet for the dog. He explains that owners can spread kibble in their yard or around their home to create a scavenger hunt.

“First, we need to validate their experience,” Dr. Campbell says. “It’s not just them giving in to their dog; there’s a real physiological component at play.”

Conversations that go beyond what dogs eat to why owners make the feeding choices they do can offer valuable insights and help veterinary professionals better support their clients. In addition, assisting owners in identifying where excess calories are coming from, paired with tools like visual aids and hands-on demonstrations of healthy weight, can make a meaningful difference in getting clients on board with managing their dog’s weight.

- Raffan, E., et al., (2016). A Deletion in the Canine POMC Gene Is Associated with Weight and Appetite in Obesity-Prone Labrador Retriever Dogs. Cell metabolism, 23(5), 893–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.012

- Wallis, N., et al., (2025). Canine genome-wide association study identifies DENND1B as an obesity gene in dogs and humans. Science. 387, eads2145. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.ads2145

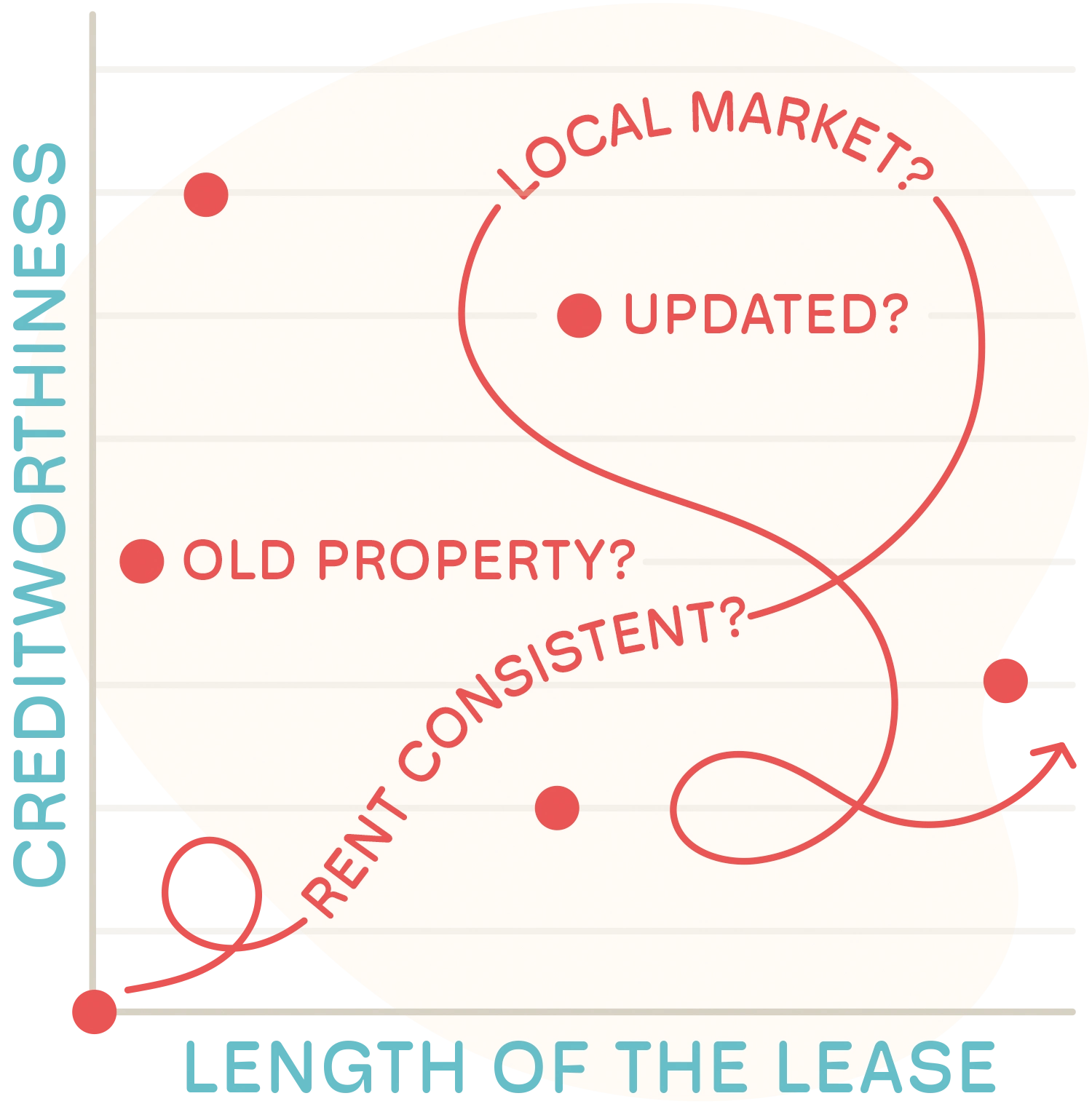

ou may have spent years running your veterinary practice, paying down debt and steadily improving your purpose-built clinic located in a desirable area, so it’s reasonable to think it would have increased in value over time. However, the economics of veterinary real estate don’t follow the logic of homeownership, or even general commercial retail…

Properties are primarily valued as income-generating assets—not simply as reflections of a building’s quality or location. Although those factors can influence the cap rate applied to those cash flows, appraisers and investors focus first on the lease structure, rent payments, tenant credit and perceived stability of income.

In fact, a practice operating out of a pristine, newly constructed clinic with below-market rent and an individual veterinarian or small group as the tenant may be valued lower than a nondescript box occupied by a national veterinary group with eight years left on the lease.

This catches many practice owners off guard when they begin preparing to divest their property or move onto a new chapter in their lives, and it leads to unrealistic expectations or strategic mistakes. Before you view your building as a financial windfall, you must see it for what it actually is.

Another factor that can move value up or down is whether the rent in your lease matches the local market. Rates that stray far above or below the going rate—a common outcome when you own and operate your practice—can undercut value, as appraisers and buyers may adjust their figures to what a replacement tenant would realistically pay.

Older properties with long-term leases and high-credit tenants can appraise higher than newer ones with below-market rent or a short lease remaining for this reason. It’s counterintuitive, but it’s consistent.

But the lease itself can erode value, too. Some triple-net leases don’t always shift every responsibility to the tenant. If you’re on the hook for liabilities like HVAC maintenance or roof repairs, they reduce net income and lower the property’s appraised value. Making improvements may not translate into a higher sale price.

If a buyer finds your lease appealing, the focus shifts to whether the building can support the future of veterinary care.

One of the most common blind spots in veterinary real estate is the assumption that what works today will still work when it’s time to sell.

Some owners overbuild, while others underinvest. Large, high-spec clinics that never reach capacity can weigh down the business through rent or debt service. Underbuilt spaces with layout problems may make it harder for a buyer to envision continued growth.

Your practice’s performance matters, too. A lease with a financially strong tenant still carries risk if the economics don’t hold. Coverage ratios—especially EBITDA to rent—help buyers assess whether the economics work.

Recruiting and retaining talent is also part of keeping a practice performing well, yet clinicians may not be attracted to an outdated building. Although facilities converted from houses were once seen as charming, they’re losing appeal as younger veterinarians look for more professional, purpose-built environments. In addition, pet owners who consider their animals to be part of their family want clinics that feel like human medical facilities.

If those challenges raise questions about your building, a relocation may strengthen your financial position and simplify your exit when the time comes. Buyers are finding value in vacant drugstores, bank branches and other commercial spaces that have been repurposed into veterinary clinics. These second-use buildings may lease below replacement cost and offer you better parking, visibility and square footage than new construction.

It’s real estate, so location still matters a lot. The more your property is aligned with what buyers want next—and not just what you’ve needed—the more value you’ll have when the time comes to sell.

Just remember that external factors like interest rates, insurance shifts and labor dynamics will also affect how your property is priced. You don’t need to think like an investor, but it helps to see what investors see—because that lens can help you get more from the building you already have.

By Rebecca Shipman

Photos provided by Dr. Emily Dohrman & Hill’s Pet Nutrition

eaching has always been a passion of mine,” recounts Dr. Emily Dohrman, DVM and manager of professional veterinary strategic initiatives at Hill’s Pet Nutrition. “So I knew that even if I pursued veterinary medicine, I wanted to incorporate education into my career.”

After earning her DVM from the University of Missouri-Columbia, Dr. Dohrman spent nearly four years in private practice in Kansas City, Missouri. During that time, she discovered how much she loved communicating with pet parents and forming relationships in the exam room.

“I found so much joy in collaborating with clients to improve their pets’ health—particularly through nutrition—and quickly knew that’s where I wanted to make a difference,” she shares.

Dr. Dohrman’s passion for teaching and nutrition eventually led her to her current role with Hill’s, where she could make an even broader impact by supporting veterinarians and advancing education.

“Nutrition is such a powerful tool; it can truly transform the lives of pets,” she states. “Early in my career, I saw firsthand how impactful nutrition conversations could be, and that has always stood out for me and really shaped my career path. The transition to Hill’s Pet Nutrition from there was a no-brainer with their scientific leadership in the field.”

With a focus on three key areas—advancing mental health and well-being, fostering leadership development, and bridging critical gaps in nutrition education—Dr. Dohrman’s role at Hill’s centers around supporting veterinary students and early-career veterinarians by driving a national strategy that makes a real difference.

“What I love most about it is being able to support the next generation of veterinary professionals, not just as students and in their early careers, but as people,” she says.

Through Hill’s student and early-career professional initiatives, they provide education and resources such as mental health support in partnership with Veterinary Hope Foundation (VHF).

“Seeing students grow in confidence, both personally and professionally, is incredibly rewarding,” Dr. Dohrman expresses. “Knowing that I’m helping prepare them to lead meaningful nutrition conversations and make a difference in their patients’ lives is what drives me every day.

Dr. Dohrman primarily works out of the Hill’s Pet Nutrition global headquarters in Overland Park, Kansas, and every day brings something new. From hosting workshops to brainstorming new ways to support students and young professionals, she is constantly inspired by the opportunity to help shape the future of veterinary medicine.

Photo by John Burns Productions

When veterinarians feel confident in discussing nutrition with clients, everyone benefits. Pets receive better care, owners feel more empowered to make informed decisions, and the veterinarian-client relationship becomes even stronger.

When veterinarians feel confident in discussing nutrition with clients, everyone benefits. Pets receive better care, owners feel more empowered to make informed decisions, and the veterinarian-client relationship becomes even stronger.

– Dr. Emily Dohrman

Despite it being foundational to pet health and playing a key role in both preventative care and disease management, one area in which students often lack confidence, Dr. Dohrman says, is in nutrition.

“At Hill’s, we’re helping to build that confidence through the Student Representative program,” she explains. “What excites me most about this approach is how it equips future veterinarians with the tools and expertise to integrate nutrition into their care from day one of their careers.”

The program provides veterinary students with immersive, hands-on training that complements their education, introducing them to leading-edge research, real-world applications and case studies that highlight the importance of nutrition in clinical practice.

“By continuing to invest in nutrition education and fostering a culture where nutrition is seen as a cornerstone of veterinary medicine,” she continues, “we have an incredible opportunity to improve patient outcomes and advance the profession as a whole.”

Veterinary medicine can be a demanding career, and as a busy mom to one-year-old twins and two Golden Retrievers, Dr. Dohrman says balancing work and family life can be a challenge, but also incredibly rewarding.

“I’m so glad my children get to see their mom be passionate about her work,” she adds.

Dr. Dohrman concludes with her advice to students and early-career veterinarians:

“Prioritize self-care and lean on the resources available to you,” she suggests. “Remember, you’re not alone, and there’s a whole community rooting for your success—both personally and professionally.”

t is widely accepted that all employees—from the newly hired to the seasoned professional—benefit from training; however, training sessions often end up lower on the veterinary practice priority list. But what is the eventual outcome of not training the team? Chaos, inconsistencies, team-member turnover, medical mistakes, loss of revenue, etc. So why do we have so much trouble doing it?

t is widely accepted that all employees—from the newly hired to the seasoned professional—benefit from training; however, training sessions often end up lower on the veterinary practice priority list. But what is the eventual outcome of not training the team? Chaos, inconsistencies, team-member turnover, medical mistakes, loss of revenue, etc. So why do we have so much trouble doing it?

For some practices, they can’t afford to have people “off the floor” and away from work, as time is limited and there are competing priorities, like emergency cases. For others, there is a lack of money, training resources or individuals to conduct the training (i.e., subject-matter experts). Or, could it be that some are just doing it wrong?

Doing it wrong? Training is training, right? There is a difference…training is not learning.1 Your team can sit through a training session and not learn what they need to perform their job. Think about your last lunch-and-learn training session. How much did the team retain? Did you need to go back and review the material again? This is an example of a failure to learn because the training session was not done the right way.

Research has found that people retain 10% of what they read and 20% of what they hear.

Instead of setting up training sessions, encourage continuous learning by creating pathways that allow each team member to take control of their learning. Enable the new hire to go back and review specific skills or knowledge. Provide a way for team members to grow their skillset without needing a formal training day. Learning pathways utilize the techniques of microlearning and asynchronous instruction to provide opportunities for team members to grow and develop at their own pace—without making them suffer through a training “dump” of information during lunch.

Learning Pathways

- Make training more flexible, on-demand and virtually accessible.

- Explain the “why”—the team needs to see how the training benefits them.

- Try micro-training formats which utilize short videos, checklists, and graphics to provide valuable and relevant content.

- Enable collaboration and feedback from colleagues.

- Create a central knowledge base where the material is archived and available for on-demand review.

- Include mixed modalities such as articles, videos, podcasts, infographics, blog posts, eLearning courses, etc.

- Prioritize recent content, especially for our rapidly changing profession.

- Provide documentation for the personnel file upon completion either through a short quiz, a sign-off when a skill is performed or the awarding of a badge.

Think of the learning pathway as the old office library of books and professional magazines upgraded to a higher standard. It still involves curating relevant material (e.g., practice SOPs, employee handbook, etc.), but it also incorporates PowerPoints, videos and web-based resources (e.g., blogs, webinars, newsletters, etc.). The material is available via online access so the “student” can independently learn the material, be it a refresher or to obtain new skills and knowledge.

There should also be a social element connected to the pathway to encourage knowledge-sharing among the team, allowing for regular updates as team members experience situations, and opportunities for asking questions. You can consider designating “go-to” team members for different topics (i.e., subject-matter experts). As a final step, the pathway should offer practice exercises and documentation for use in personnel files.

For example, a new hire can begin the learning process by accessing a folder via the online portal. There they can read the employee handbook, learn more about the hospital, complete paperwork, understand safety protocols and submit any questions. Now, instead of the practice manager doing all that on the new hire’s first day, the two can discuss any questions and concerns, or the new hire can receive guidance and feedback from the manager.

From there, the pathway can provide educational goals just like your phase-training schedule—only now, instead of a notebook filled with paper, it is online. For example, perhaps the CSR phase training begins with telephone skills or check-in procedures. In addition to your training handbook and checklist, video and webinar resources are added to your training material in an online format.

There is so much information “out there” that it can be overwhelming, but there is opportunity to delegate and develop others on your team. For example, assign the surgery nurse the role of updating resources and materials related to surgery. Or, a CSR may curate videos on how to deal with demanding clients. Your team is now actively involved in gathering material, reviewing it, getting it approved and placing it in the learning pathway for everyone to use.

According to the Harvard Business Review, creating content is replaced with curating content, incorporating information from different sources and in different formats to build a learning pathway.2 For some of the information, there is no need to reinvent the wheel—you just need to find it online and incorporate it into your training resources. However, it’s important to evaluate the current offerings from several different sources as you build different pathways.

For example, some providers of web-based learning resources are ACT Online Training, Fear Free Certification Program, AVMA PLIT web-based training modules on safety, AAHA Learning, Cat-Friendly Veterinary Professional Certificate Program, various corporate e-learning modules (e.g., Zoetis, PSIvet, Merck, etc.) and more.

Training doesn’t have to be time-constrained and boring. Learning is exciting when it is easy to access, relevant, current and engaging. Take the time to understand the needs of the business and each team member, identify where there are gaps in skills or knowledge, get the team involved, curate the resources, create the pathways and let the learning begin!

- The Difference Between Training and Learning. Advanced Business Learning. https://advancedbusinesslearning.com/2016/07/20/the-difference-between-training-and-learning/

- Zao-Sanders, M. and Peake, G. (2022, February 3). Creating Learning Pathways to Close Your Organization’s Skills Gap. The Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2022/02/create-learning-pathways-to-close-your-organizations-skills-gap

re you someone who gets superb results with patients or clients but puts yourself on the back burner? In this profession, we often lose ourselves in the service of others. In addition, reprioritizing your needs is uncomfortable, awkward and, at best, can feel like a clunky effort. And so we think, let’s stay hidden, let’s put others out front.

A few things have to happen to break that cycle. First, you have to give yourself permission—because even if others give it to you, it’s not until you believe it for yourself, through yourself, that there is a shift.

Second, you have to be ready. And there’s no timeline for how long that might be—a month, a year, a good sleep—just start cultivating that internal infrastructure. What will it take? What might you lose? What might you gain? How do you function? Preparing for the lifelong marathon of managing and navigating your own health and well-being in an aging body and in a demanding profession is not easy.

Are you a one-day-at-a-time person? Think of people who choose to stay sober. They make that choice every single day, and even throughout the day. This journey is no different. There will be temptations that spark with certain triggers, and when your resilience is testing and your personal resources are depleted, you will be challenging your previous default.

Defaulting to fast food or being a couch potato when you are in a state of distress? Take time to ponder how you can reset that default. What logistics have to be in place for you to get off that couch and begin getting your body condition to improve, slowly but surely? What would need to happen in moments of worry for you to lift the dumbbells instead of the bag of chips? As we age (no matter your sex, but absolutely for the nearly 90% of women in this field), building strength to prevent injury and illness later on is paramount.

Let’s say you’ve got your nutrition and body condition plan in your mind’s eye—your vision—and even better if you have it written down on paper. Now it’s time to experiment. Add stuff in, take stuff out, do more of this, less of that. Keep leveling up. It’s not one thing, like most things in life, it’s a recipe. Consult professionals if and when it’s time.

besity affects well over a third of dogs in North America, and its prevalence continues to climb annually.1 Pet owner awareness of the body condition of their pets is also growing with 35% of dog owners in 2024 categorizing their pet as being overweight or obese, doubling from the pet owner awareness reported in 2023.1

Conversely, only 27% of dog owners recall having their veterinarian provide them with a distinct body condition score for their dog.1 Some veterinary professionals acknowledge hesitation due to perceived owner discomfort about pet obesity discussions, though. In one survey, 69% of pet owners reported they did not feel uncomfortable with being told their pet needed to lose weight.1 These findings reiterate the importance of veterinary professionals to continue to have conversations about weight management in their patients.

For the modern veterinary professional, weight management must go far beyond simple calorie restriction. Obesity is now recognized as a systemic, chronic inflammatory disease that impacts all major organ systems—often before overt clinical signs become apparent. The veterinary role now involves not just addressing excess weight, but also identifying and managing the hidden, potentially irreversible complications that often develop in overweight and obese dogs.

A focused OA assessment confirmed mild-to-moderate pain with decreased activity at home. The team initiated a structured weight-loss plan, switching Charlie to a prescription, high-protein/fiber, calorie-controlled diet with strict treat limits. NSAID therapy was started, and a rehabilitation consult was arranged for a tailored exercise regimen. After three months, Charlie’s weight had decreased by 2 kg, BCS improved and activity scores markedly increased. His owner noted greater playfulness, better mobility and a return to favorite activities.

This example highlights both the common denial of obesity’s impact and how a multimodal approach can reverse an accelerating cycle of pain and disability.3

Obesity in dogs is fundamentally a metabolic disease, driven by chronic overnutrition and reduced physical activity. Excess adipose tissue is not inert—it’s hormonally active, secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) and adipokines (e.g., leptin, resistin) that trigger a state of chronic low-grade inflammation. This systemic inflammation underlies many of the early, hidden complications of obesity. Key metabolic consequences include:

- Insulin Resistance/Prediabetes: Obese dogs show reduced sensitivity to insulin, as evidenced by impaired glucose tolerance. Persistent insulin resistance increases the risk for overt diabetes mellitus (especially in breeds like Miniature Schnauzers, Dachshunds and Poodles).4,5

- Dyslipidemia: Elevated triglyceride and cholesterol levels are frequently found in overweight dogs. This not only increases the risk of pancreatitis, but also accelerates the development of atherosclerotic changes in blood vessels—though true atherosclerosis is less common in dogs compared to humans.6

- Metabolic Syndrome: A cluster of abnormalities—including abdominal obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia and impaired fasting glucose—may be present even in preclinical obese dogs, mirroring human metabolic syndrome.

- Pancreatitis & Hepatic Lipidosis: Hyperlipidemia in obese dogs predisposes to pancreatitis, a potentially life-threatening complication. Hepatic lipidosis (fatty liver) and mild elevations in liver enzymes can be detected in overweight patients, even before clinical signs emerge.7

- Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation: Adipose-derived cytokines maintain oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction, further driving metabolic derangement.

A clinical approach should include annual or more frequent metabolic screening (fasted glucose, lipids, ALT/ALP) for any dog with BCS >7/9 or rapid weight gain. And in overweight patients, even mild “out-of-range” results should prompt early intervention and close monitoring.

Obesity imposes significant hemodynamic and respiratory burden—even without clinical “heart disease” or apparent respiratory distress. Major cardiovascular risks include:

- Increased Cardiac Workload: Excess body fat increases blood volume and cardiac output requirements, leading to ventricular remodeling and, over time, possible cardiac insufficiency.

- Systemic Hypertension: Obese dogs are at higher risk for hypertension, which predisposes to target-organ damage (kidney, eyes, heart, brain).8

- Arrhythmias: Although less common, abnormal fat deposition around the heart may disrupt normal conduction, occasionally increasing arrhythmogenic risk in severely obese dogs.

Respiratory complications include:

- Decreased Pulmonary Compliance: Fat accumulation in the thorax and abdominal cavity restricts diaphragmatic motion, reducing tidal volume and vital capacity.

- Exacerbation of Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS): Even slight weight gain in brachycephalic breeds can convert a subclinical case to a significant one, resulting in distress or crisis, especially under anesthesia.

- Increased Anesthetic Risk: Studies show that obese dogs have delayed recovery and greater risk of perioperative hypoxia, aspiration and post-anesthetic complications.9,10

A clinical approach should include routine blood pressure screening in obese or at-risk patients (age >7 years, BCS ≥6/9 or breeds predisposed to hypertension). Baseline thoracic auscultation, and in some cases imaging, for panting, “exercise intolerance” or “nothing more than old age” complaints should be considered. In addition, pre-anesthetic evaluation should assume increased respiratory and cardiac risk, necessitating conservative sedation protocols and vigilant monitoring.

- Early-Onset Osteoarthritis (OA): Overweight dogs develop OA at a younger age and with more severe radiographic and clinical changes. Weight-induced mechanical overload and the inflammatory cytokine environment promote cartilage degeneration, synovitis and pain.3

- Ligamentous Injuries: Obesity is a strong risk factor for cranial cruciate ligament rupture and patellar luxation.11,12 Surgical outcomes are often poorer in overweight dogs, with longer recovery times and more complications.13

- Reduced Mobility & Sarcopenia: Obese dogs are less willing or able to exercise, which rapidly leads to muscle wasting (“sarcopenia”) and further exacerbates joint instability and pain. This can become a vicious cycle—weight restricts movement, which increases fat and deteriorates muscle and joint health.

- Pain Masking: Owners often attribute reduced activity, reluctance to climb stairs or difficulty rising to “normal aging,” failing to recognize that these are cardinal signs of OA pain exacerbated by excess weight. Clinical pain scoring systems, such as LOAD or CBPI, are valuable for monitoring.

A clinical approach should include performing thorough orthopedic and neurologic examinations in any overweight or obese dog at every annual and sick-patient visit—even subtle gait changes may represent significant pain. Early, multimodal OA therapy (NSAID, weight loss, joint diets, rehabilitation) should be initiated at the first sign of pain or joint swelling. Even weight loss as modest as 6% can significantly reduce lameness and increase mobility.14

- Nutritional Therapy: Prescription hypocaloric diets high in protein and fiber, and strict treat control are paramount. Omega-3 (EPA/DHA) supplementation is recommended for anti-inflammatory and metabolic support, targeting a minimum daily dose of 100 mg/kg EPA/DHA.3

- Pain Management/OA Therapy: Early, sustained NSAIDs are cornerstones for obese dogs with OA. Experts in orthopedic disease recommend starting with one to three months of daily NSAID therapy at initial OA diagnosis before considering tapering, with moderate to severe cases often requiring life-long daily treatment.3

- Physical Rehabilitation: Tailored exercise plans can help restore function and aid safe activity, minimizing injury risk as weight is reduced.

- Routine Monitoring: Rechecks should be performed every two to four weeks initially, with adjustment based on weight, BCS, labs and response to therapy.

Daisy’s plan included a calorie-restricted diet, increased walk frequency, and regular monitoring of blood pressure and cardiac function. When rechecked four months later, Daisy had lost 1.5 kg, her blood pressure had normalized and her stamina had improved. Early cardiovascular screening and intervention prevented progression to more serious disease.

Encourage owners to track treats and activity using journals or apps, celebrate small wins and tailor follow-up to reinforce momentum. Proactive, nonjudgmental and consistent messaging is essential for long-term success.

Obesity is a serious medical disease that demands immediate, coordinated and comprehensive intervention. By recognizing and treating its hidden complications—metabolic, cardiovascular and orthopedic—alongside sustained weight management, veterinary teams can truly improve both the quality and length of their patients’ lives.

- 2024 Pet Obesity and Nutrition Survey Highlights. (2025). Association for Pet Obesity Prevention. https://www.petobesityprevention.org/2024-survey

- Kealy, R., Lawler, D., Ballam, J., et al. (2002). Effects of diet restriction on life span and age-related changes in dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 220(9), 1315-1320. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.2002.220.1315

- Cachon, T., Frykman, O., Innes J., et al. (2023). COAST Development Group’s international consensus guidelines for the treatment of canine osteoarthritis. Front Vet Sci. 10:1-23. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2023.1137888

- Qu, W., Chen, Z., Hu, X., et al. (2022). Profound perturbation in the metabolome of a canine obesity and metabolic disorder model. Front Endocrinol. 13:1-16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.849060

- Behrend, E., Holford, A., Lathan, P., et al. (2018). 2018 AAHA Diabetes Management Guidelines for Dogs and Cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 54:1-19. https://www.aaha.org/wp-content/uploads/globalassets/02-guidelines/diabetes/2018-aaha-diabetes-management-guidelines-2022-update.pdf

- Söder, J. (2018). Metabolic variations in canine overweight: Aspects of lipid metabolism in spontaneously overweight Labrador Retriever dogs. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Sueciae. 62. https://pub.epsilon.slu.se/id/document/16584183

- Belotta, A., Teixeira, C., Padovani, C., et al. (2017). Sonographic Evaluation of Liver Hemodynamic Indices in Overweight and Obese Dogs. JVIM. 32(1):181-187. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jvim.14883

- Gomes, C., Morais, C., Lima, S., et al. (2025). Canine Obesity: Contributing Factors and Body Condition Evaluation. Pets, 2(2), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/pets2020022

- Love, L., Cline, M. (2015). Perioperative physiology and pharmacology in the obese small animal patient. Vet Anaesthesia Analgesia. 42:119-132. https://doi.org/10.1111/vaa.12219

- Redondo, J., Otero P., Martinez-Taboada F., et al. (2023). Anesthetic mortality in dogs: A worldwide analysis and risk assessment. Vet Record. 195(1):e3604. https://doi.org/10.1002/vetr.3604

- Adams, P., Bolus R., Middleton, S., et al. (2011). Influence of signalment on developing cranial cruciate rupture in dogs in the UK. J Small Anim Prac. 52(7):347-352. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5827.2011.01073.x

- Andrade, M., Slunsky, P., Klass, L., Brunnberg, L. (2020). Risk factors and long-term surgical outcome of patellar luxation and concomitant cranial cruciate ligament rupture in small breed dogs. Veterinarni Medicina. 65(4):159-167. https://vetmed.agriculturejournals.cz/pdfs/vet/2020/04/02.pdf

- Fitzpatrick, N., Solano, M. (2010). Predictive variables for complications after TPLO with stifle inspection by arthrotomy in 1000 consecutive dogs. Vet Surg. 39:460-474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-950X.2010.00663.x

- Marshall, W., Hazewinkel, H., Mullen, D., et al. (2010). The effect of weight loss on lameness in obese dogs with osteoarthritis. Vet Res Commun. 34(3):241-253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11259-010-9348-7

SEE HOW MANY YOU CAN DO!

with sustainability

this Thanksgiving.

Thanks for reading our October / November 2025 issue!